In 2017, the Special Evaluation Office of the Belgian Development Cooperation commissioned an impact evaluation of Belgian higher education cooperation, including institutional cooperation and scholarships going back as far as 2008. This evaluation has both a formative and a summative objective. The formative component of the evaluation analyses the extent to which impacts of higher education cooperation are evaluable with state-of-the-art evaluation designs. The summative component of the evaluation analyses the impact of all scholarships and select cooperation projects and programmes in the period subject to evaluation. In this blog post, the evaluation team shares some aspects of the evaluation design adopted for measuring the impact of scholarships. More specifically, we address how robust impact measurement may be achieved when a panel survey is not feasible.

Panel surveys collect information from the same individuals at multiple points in time to capture long-term changes. To measure the impacts of scholarships on individual trajectories (e.g. on professional development), panel surveys are considered the most robust design. This is because information collected in real time about the situation before, during, and after participation in a scholarship programme is considered more reliable than information based on recall. However, it is often not feasible to implement panel surveys in impact evaluations, as evaluation assignments have to be completed in a given timeframe that does not allow for data collection over the course of several years. This is precisely the situation we are facing with the impact evaluation of Belgian higher education cooperation.

Evaluation design

Against this background, we have developed an evaluation design which enables us to capture the longitudinal development of scholarship recipients without implementing a panel survey. This is made possible by the length of the period subject to evaluation (from 2008 onwards) and the comparatively high number of (graduated) scholarship recipients. Our concept revolves around the idea of artificially approximating a longitudinal design. Instead of following the development of one cohort over time, we gather data that enables us to construct a ‘stratified cohort’. This is an approach we have successfully tested in previous evaluations on behalf of the German Ministry for Development Cooperation (BMZ) and the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). To ensure the approach is appropriate in the context of the Belgian university development cooperation, we carried out a Delphi survey with Belgian and international experts which provided inputs for finalising the evaluation design.

The evaluation on the basis of a stratified cohort is done in two steps:

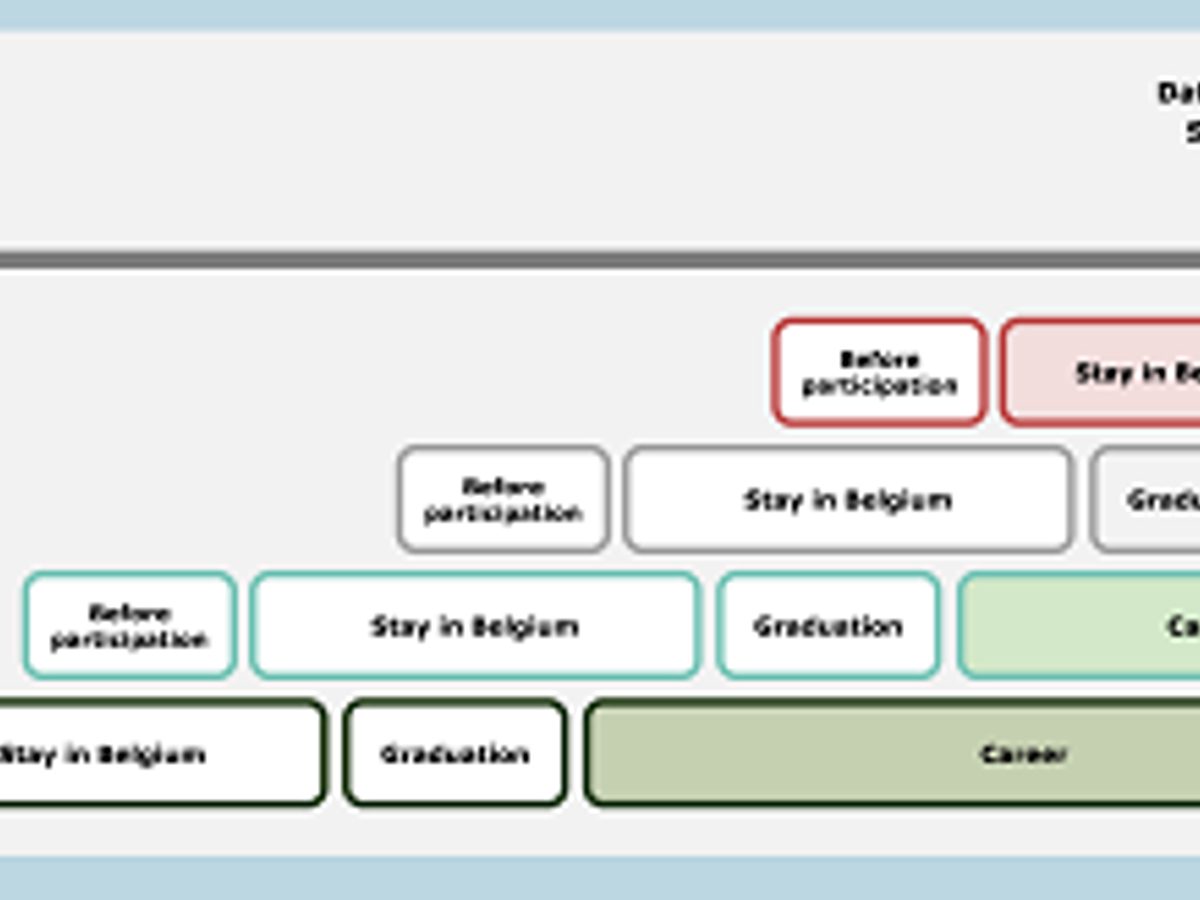

In a first step, data is collected at one single point in time (September 2017) from individuals who received their scholarship in different years. The respondents to the survey are thus at different stages in their scholarship experience (e.g. during and after) at the moment of data collection (see figure 1). Some of the survey questions (e.g. on competencies) are asked to all participants, whereas questions regarding the impact of the scholarship programme (e.g. application of competencies in professional life) are only asked to participants who have already graduated and started a job.

In a second step, the data collected is consolidated and presented to show the evolution in the situation of participants during the scholarship, and at different stages after having completed the scholarship (see figure 2). The condition for this is that there is a statistically robust similarity between the different cohorts. The analysis of the evolution of scholarship recipients over time makes it possible to evaluate the scholarship programmes against the intended impacts as formulated in the Theories of Change of the two Belgian umbrella organisations for university development cooperation (VLIR-UOS and ARES). In these Theories of Change, scholarship schemes intend to unfold short-term impacts at individual level, and mid- and long-term impacts at institutional level and society-level. In this regard, short-term impacts in ARES and VLIR-UOS scholarship schemes are, for example, the improvement of the students’ employability and their ability to apply newly acquired skills and knowledge in relevant sectors. In the mid- and long-term this should ultimately benefit organisations’ performance in relevant sectors. Moreover, the graduated scholarship recipients should act as change agents and contribute to solving challenges in the field of development.

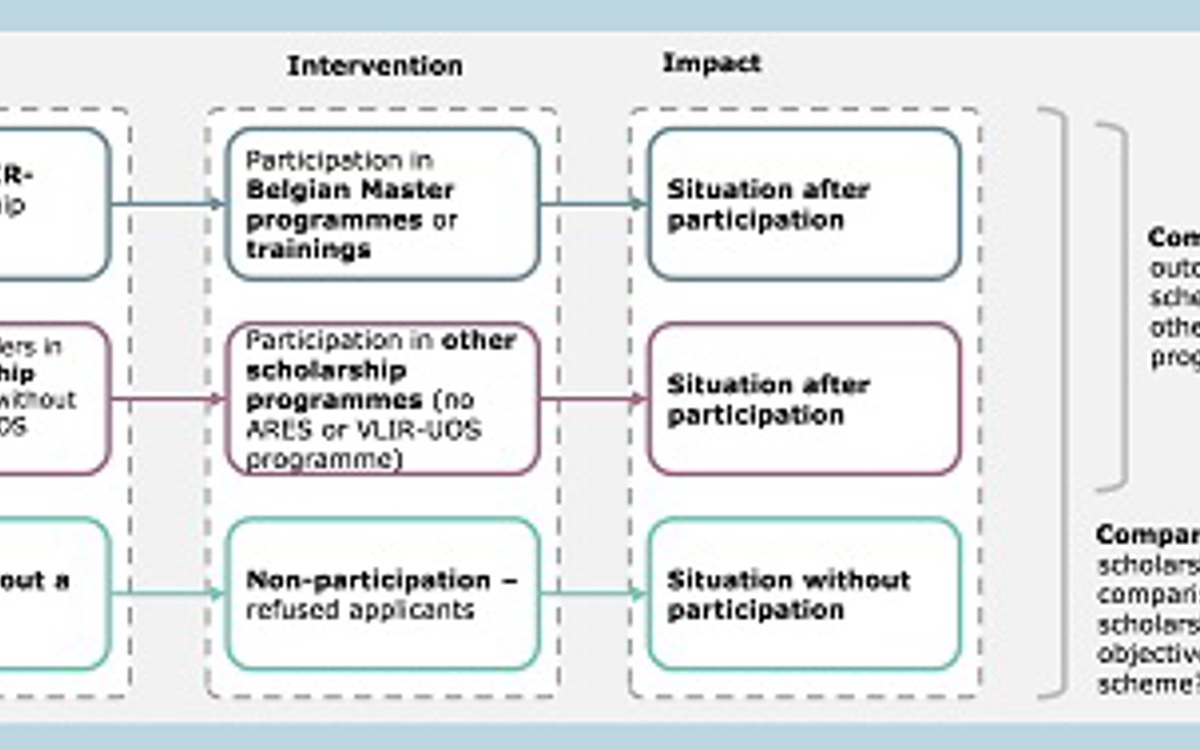

To further strengthen the evaluation design and analyse to what extent the impacts observed at the level of the scholarship recipients have unfolded due to their scholarship, we combine this approach with a quasi-experimental design. In this quasi-experimental design, the survey will not only be administered to scholarship recipients, but also to those individuals who applied for the scholarship programme and landed on the reserve list (e.g. due to limitations in financial budget). We expect that within this comparison group of individuals who did not get a scholarship from VLIR-UOS or ARES, there will be two sub-groups. Individuals who did not receive a scholarship at all, and individuals who ended up acquiring a scholarship from a different organisation.

Figure 3 gives an overview of the different groups and the comparison that can be drawn on this basis. Comparison 1 is a between-programme counterfactual that analyses how the outcomes and impacts of the Belgian scholarship schemes rank in comparison with other, similar scholarship programmes. Comparison 2 is conditional counterfactual which analyses where scholarship recipients rank in comparison to individuals who did not receive a scholarship.

In sum, the adopted evaluation design combines a counterfactual approach with a generative / mechanisms and regularity approach to causal inference. The counterfactual approach relies on the comparison of a ‘treatment group’ who participated in the programmes, and a comparison group that did not. The generative / mechanisms approach relies on identifying the ‘causal mechanisms’ that generate the intended impacts. For this, a Theory of Change of the Belgian scholarship schemes was developed, and the survey questions are geared towards finding out if the changes unfold as described in the Theory of Change.

In addition, we will also carry out qualitative interviews with scholarship recipients during field missions in three selected countries to further analyse the plausibility of the causal hypotheses underlying the Theory of Change. Finally, the regularity approach assesses causality of impact depending on the frequency of association between a given cause and effect. In this case, the high numbers of participants in the scholarship schemes gives us the possibility to draw conclusions from the survey. The possibility to draw conclusions about impact (short-term, mid-term, long-term) will depend on the response rate per cohort. It is our hope that by combining these approaches, we will be able to produce a clear and robust evaluation of the impact of the Belgian university development cooperation scholarships.

Photo by Headway on Unsplash

Lennart Raetzell and Olga Almqvist

The Measuring Success blog series draws from the ACU's experience in scholarship design, administration, and analysis, and our connections in the sector, to explore the outcomes of international scholarship schemes for higher education.