The resurgence of New Zealand’s Māori language is a story of hope and the power of perseverance.

By Hēmi Kelly, Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand

As many indigenous languages struggle for survival, the resurgence of New Zealand’s Māori language is a story of hope and the power of perseverance – and universities are playing their part.

By Hēmi Kelly, Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand

It’s an exciting time for the Māori language in Aotearoa New Zealand. Once confined to certain spaces or groups of people, today the language can be seen, heard, and spoken across mainstream media and public domains, from Disney and Google to Parliament House. And what’s more, people are queuing up to learn it.

If you’re not familiar with the Māori language, let me give you a brief overview. Māori, commonly referred to as te reo Māori (the Māori language), is the indigenous tongue of our island nation and a member of the eastern Polynesian languages. Māori falls behind English as the second most commonly spoken language in New Zealand and, after 32 years of having official status, the national debate continues on whether or not the language should be compulsory, to some degree, in schools.

At present, we’re anticipating the results from the 2018 census to understand more about the population of Māori speakers. The 2013 census recorded that nearly 4% of the population could speak Māori, but to what degree, we don’t know. Te Kupenga, a more detailed survey conducted the same year, found that more than 20% of Māori could speak the language fluently. Irrespective of the statistics to come, the future is bright, given that a quarter of the first figure were children.

In seeing the statistics, we understand that the language is far from safe. However, if we take the numbers out of the equation, we see a rather different picture. The popularity of the Māori language has in fact grown substantially in recent years. It seems as though the efforts of the past four to five decades have reached a tipping point whereby New Zealand is now experiencing a social shift towards the language. This public swell of interest has created waiting lists at tertiary institutions across the board, including Auckland University of Technology (AUT).

Listen, learn, love

This will be my sixth year lecturing in Māori at AUT. We don’t offer a major in the language, but any of the seven Māori language courses we do offer can be taken as electives to form a minor or simply as a programme of interest. The courses start at a very basic introductory level and progress into full immersive learning.

In the time I have been at AUT, I have seen enrolments across all seven courses go from 594 students in 2014 to 1,595 in 2018. In that same space of time, the Māori language teaching team has more than doubled in an attempt to cater to demand.

This popularity boom is also reflected in our students who come from diverse ethnic and professional backgrounds, and range in age and understanding. But all share a desire to deepen their connection with the language.

Alongside formal teaching and learning, a number of initiatives are taking place at AUT to revitalise the language in the community. AUT is home to Te Ipukarea, the National Māori Language Institute. Te Ipukarea is at the forefront of showcasing how the use of technology and digital platforms that are accessible, interactive and fun for all can support the revitalisation of the Māori language.

With over 300,000 visitors each month, Te Aka – an online Māori dictionary – is one of the institute’s most popular resources. It was one of the fruits of the lifelong labour of the late AUT Professor John Te Murumāra Moorfield, affectionately known as Mu or Pāpā John. Mu, quite literally, worked on updating the online dictionary until he passed away in 2018. A new feature of the website is audio recordings for each word, giving users the opportunity to hear words pronounced correctly by native speaking elders. Te Ipukarea updates the dictionary regularly with new entries – a task with no end point as we endeavour to keep up with the technological era in which we live.

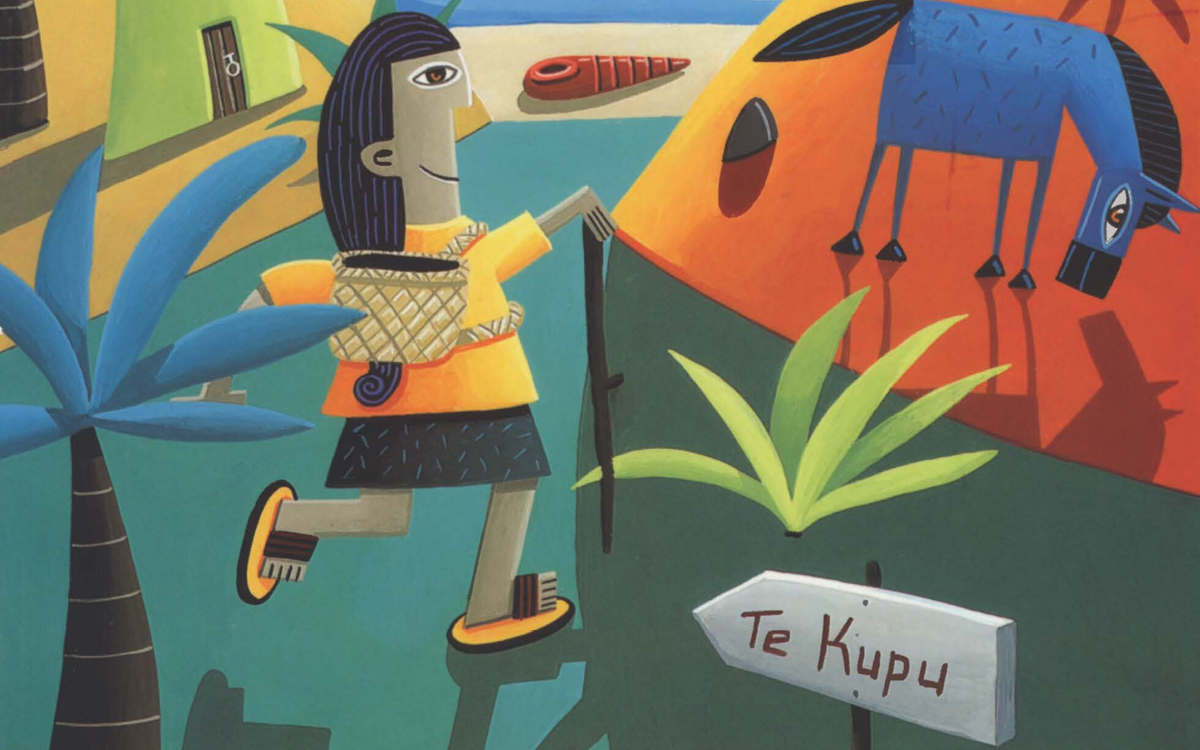

Another digital resource that stems from the Te Aka online dictionary is the interactive mobile app Kupu (which means ‘word’). Kupu helps people learn Māori words by photographing objects around them. When an image is submitted, the app uses image recognition to identify the object and provides the Māori for that object and other related words. You can download Kupu for free from the Google Play Store or the iOS App Store and start learning now!

More than words

Two new books published from within AUT recently joined these digital tools in the growing collection of Māori language learning resources. He Kupu Tuku Iho: Ko te reo Māori te tatau ki te ao is a discussion on a range of topics pertinent to the Māori world, including language, cultural concepts, humour, and more. The chapters are interview exchanges between the authors, Professor Wharehuia Milroy and Sir Timoti Karetu. Their discussions are couched in the musings and memories of their lives – a tapestry of spoken dialogue that can occur only between native speakers. A monolingual Māori language text like this is designed for speakers or advanced learners of the language.

At the other end of the spectrum is A Māori Word a Day, a book I published last year. This book is designed for those at the beginning stages of their learning journey, and offers an easy entry into the language. Each of the 365 words comes with English translations, word categories, interesting background information, and sample sentences.

Nurturing more young writers is important to sustaining the vitality of Māori literature into the future: He Huatau Auaha is a creative writing competition for children that calls for submissions only in the Māori language. The unique Māori perspective in storytelling provides a forum for young people to express their ideas and creativity through writing, and the last competition attracted more than 90 submissions from 16 schools throughout New Zealand.

Te Reo o te Pā Harakeke is another AUT initiative focused on children and families. This three-year research project seeks to understand the factors that contribute to successful intergenerational transmission of the Māori language in the home. The distinctive element of this project is its focus on effective strategies, methods, and resources for establishing and maintaining Māori as the first language in the home, and providing empirical evidence on the obstacles that exist.

These projects and initiatives within AUT are a reflection of the Māori language landscape in a number of tertiary institutions across the country. I’m excited to see what the future holds and how the Māori language and culture will continue to enrich the lives of New Zealanders and attract others to our island nation at the bottom of the Pacific.

Hēmi Kelly is a Lecturer in the Te Ara Poutama Faculty of Māori and Indigenous Development at Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand.

Visit www.tewhanake.maori.nz to access interactive resources for learning and teaching the Māori language.