A sleeping language awakens in Singapore. By Kevin Martens Wong

Three years ago, a student at the National University of Singapore embarked on a journey to find out more about the lost language of his great-great grandparents. What transpired was a voyage of discovery and revitalisation beyond anything he’d imagined.

By Kevin Martens Wong

Kristang, my critically endangered heritage language, is today spoken by only 100 or so people in my home country of Singapore. The language and I are both descended from the Portuguese conquest of Melaka in 1511 and subsequent intermarriages between arriving Portuguese colonisers and local Malay residents. Those unions produced both a unique ethnic identity – the Portuguese Eurasians of Malaya – and their language, Kristang. Today, you can find Portuguese Eurasians all over southeast Asia, Australia, and the rest of the world.

Kristang, unfortunately, does not have the same geographic reach. It is spoken today in only a handful of cities and territories, including Singapore, Melaka, Seremban, Kuala Lumpur, and Perth, and its use is declining in all of these. In Singapore especially, Kristang’s decline has been steep, with the language losing significant ground to English when Singapore and Malaysia came under British rule.

After Singapore gained independence in 1965, English became entrenched as the sole language of education and the major language used in most spheres of society. Intergenerational transmission of Kristang ceased almost completely.

My great-great-grandmother Edith Klass, who passed away the same year that Singapore became independent, was the last person able to speak Kristang fluently in my family. Today, most Eurasian families in Singapore speak English at home. Few, if any, of the younger generation know much of Kristang, other than a choice few exclamations and names of food. It is not surprising to encounter younger Portuguese Eurasians who have no idea Kristang even exists, not to mention younger Singaporeans, as awareness of Kristang and many of Singapore’s minority languages remains low.

I was one of these younger Portuguese Eurasians until January 2015, when, as a second-year student at the National University of Singapore (NUS), I discovered that Kristang still existed. I also found out that my grandparents could still speak a bit of the language! My discovery came while researching an article for a linguistics publication called Unravel. Together with three other Unravel editors, I headed up to Melaka (often known by its old colonial name of Malacca) in Malaysia to meet some of the people leading more established revitalisation efforts for the language there. Inspired by what they were doing, we decided to return to Singapore to see what we could do for Kristang here.

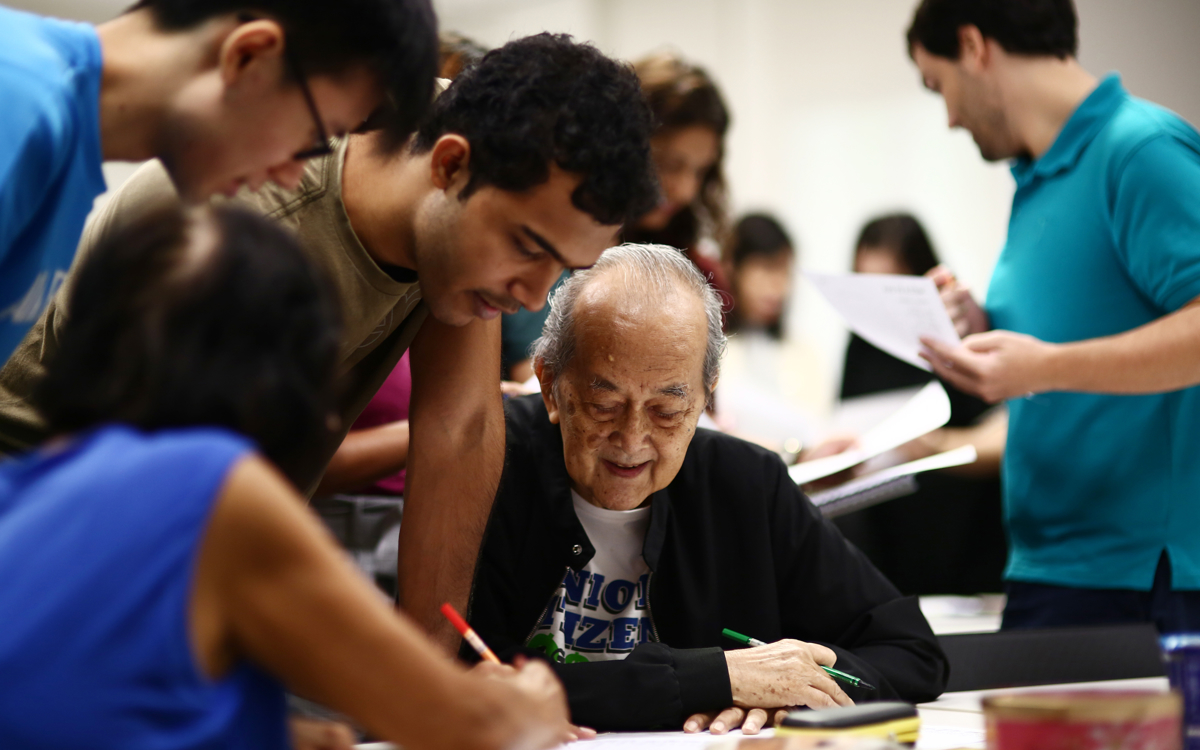

As part of one of my modules at NUS, I initiated a project to locate speakers of the language in Singapore, and began learning it from those I found, as well as from my own grandparents. I then met my 14th Kristang collaborator: Bernard Mesenas, a retired primary school teacher. Bernard encouraged me to move beyond just documenting and archiving Kristang, and to begin revitalising it by teaching and leading language classes in Singapore.

I was apprehensive – I was not a native speaker of the language. But Bernard’s insistence that someone had to do something before the language he cared about disappeared was powerful and profound. We eventually agreed that we would lead classes together, with me teaching at the front and Bernard sitting among the learners, providing input and correction where necessary. Importantly, the class would be free to ensure that as many people as possible could join, and would also be interactive and activity-oriented so as to increase people’s conversational competence as quickly as possible.

The first ever Kodrah Kristang (Awaken, Kristang) class ran in early 2016. It was held in a university canteen at NUS with 12 students plus Bernard and myself leading the class. Things immediately began looking up that same weekend, when my college at NUS agreed to host the remaining seven sessions of the class. However, the truly amazing thing was what came after the classes concluded: demand for a second iteration of Kodrah Kristang surged, especially among Portuguese Eurasians.

Energised by the interest, I began to develop concrete plans for a grassroots-led initiative in Singapore, centred around a series of structured adult classes and a long-term revitalisation plan for the language. Although my vision was mostly aspirational, I hoped that the enthusiasm for a second round of classes meant that at least some of what I articulated would eventually come to fruition – particularly increasing awareness of Kristang’s existence, and the development of a core group of new Kristang speakers who would be able to take the language forward into the future. Little did we know that things would evolve beyond even my wildest imaginings.

Today, three years later, we have just begun our 11th iteration of our hugely popular beginner’s class, which has attracted more than 500 students since that first class in 2016. Twenty-six amazing students have completed all eight levels of our adult classes, having learned Kristang with us for more than two years.

The initiative has scored a number of record firsts, including Singapore’s first ever Kristang Language Festival, a Kristang boardgame, and an online dictionary – the latter led by Luís Morgado da Costa, a researcher at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University.

The Kodrah Kristang core team remains multiethnic and vibrant, and we now run classes at community centres islandwide. Most importantly, through all of this, awareness of Kristang in Singapore has skyrocketed, with the initiative featured by the BBC and Agence France-Presse, as well as other local and international media outlets. We have also served as the inspiration for a number of blossoming revitalisation initiatives for other minority languages such as Baba Malay, Boyanese, Minangkabau, Maquísta, and Cannanore Portuguese Creole.

Of course, full revitalisation remains an uphill challenge. The rapid pace of life that the 21st century demands means that Kristang will always be in the shadow of larger, more ‘economically useful’ languages. However, the meteoric success of our initiative provides hope to all of us who now speak a little of our beautiful heritage language. Yo sperah tudu jenti logu beng prendeh papiah Kristang – I hope everyone will come and learn to speak Kristang.

Kevin Martens Wong is Kabesa (Director) of Kodrah Kristang, the initiative for the revitalisation of the Kristang language in Singapore. He started Kodrah Kristang while a student at the National University of Singapore.