Why a nation’s ability to build on the knowledge that already exists among its people is vital to its development. By Hassan O Kaya and Mayashree Chinsamy, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

A nation’s ability to build on the knowledge that already exists among its people is vital to its development.

By Hassan O Kaya and Mayashree Chinsamy, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

A common criticism levelled against universities in Africa is that they remain rooted in Eurocentric worldviews and traditions at the expense of Africa’s own rich history of ideas and intellectual development. The significance of African worldviews – our ways of knowing, knowledge production, languages, philosophies, and the lived experiences of Africans themselves – have been sidelined, creating a disjuncture between learning and living, and making higher education too remote from the developmental challenges facing our communities.

The dominance of western knowledge created the view that there is only one social reality and one system of knowledge: that of the west. This is exemplified by the teaching of social sciences and humanities, in which social, economic and political thought remains entrenched in the methods, concerns and experiences of 19th century western Europe and north America. Africa’s contributions over centuries to history, science, technology, innovation, and civilisation are openly neglected, while the pursuit of academic excellence and theory is prized above local relevance and practice. This is despite the fact that the livelihoods of many Africans still depend on indigenous knowledge systems.

Yet there is a growing realisation that a nation’s ability to use and build on the knowledge systems that exist among its people is as vital to socioeconomic development as physical and financial resources. Learning from what local communities already know also creates an understanding of local conditions and provides important context for any activities designed to support them.

It was for these reasons that, in 2004, the South African government adopted the National Indigenous Knowledge Systems Policy, which mandated the advancement of indigenous knowledge systems in universities as a key component of human capital and the transformation of higher education to meet developmental challenges. Integrating indigenous knowledge in this way not only helps to protect and promote this valuable knowledge, it also acknowledges the plurality of knowledge systems and their contribution to the world.

An authentic expression of ourselves

Indigenous knowledge refers to the longstanding traditions and practices of indigenous communities and cultures. It encompasses the skills, innovations, wisdom, teachings, beliefs, languages and insights of the people, produced and accumulated over centuries and used to maintain or improve their ways of living.

The depth of these knowledge systems, rooted in the long inhabitation of local ecosystems, offers lessons that can benefit everyone as we search for a more satisfying and sustainable way to share our planet. In many communities, especially in rural areas, indigenous knowledge systems are at the heart of survival and inform decision-making about every aspect of day to day life – from nutrition and reproductive health to environmental management and conflict resolution. This knowledge is community-based, accessible, affordable, and culturally-sensitive – and hence sustainable – and may hold solutions to our most pressing global challenges. Yet it remains an underutilised and even marginalised resource.

The DSI-NRF Centre in Indigenous Knowledge Systems (CIKS) is a partnership between five South African universities: the University of KwaZulu-Natal as the hub, North West University, the University of South Africa, the University of Limpopo, and the University of Venda. We are predominantly institutions located in or around rural provinces, where a majority of people depend on indigenous knowledge systems for their livelihoods.

Our mandate is to preserve, promote, and protect indigenous knowledge on its own merits. We believe knowledge is culturally and place-based: there is no universal reality or value-free science, and this calls for a paradigm shift in higher education – one which acknowledges that we are living in a polyepistemic world, in which knowledge systems are complementary rather than competitive. African indigenous knowledge, then, should not only be seen as an ‘alternative’ knowledge system but as one domain of knowledge among others.

Our understanding of indigenous is not necessarily what is ‘traditional’, but rather whatever the African people, in their diverse cultures and ecosystems, consider to be an authentic expression of themselves. This means taking the cultural realities of African societies as they are, and not as other cultures might want them to be.

Africa’s history of slavery and colonisation, including apartheid, destroyed a sense of confidence among African peoples. But building on our rich sources of indigenous knowledge and ideas, especially within education, promotes self-reliance and begins to restore this lost confidence, particularly among marginalised groups. Promoting indigenous knowledge in universities enables South Africa and Africa as a whole to enter the global knowledge economy on our own terms, rather than those dictated by others.

Embracing Ubuntu

The Centre in Indigenous Knowledge Systems works to transform higher education in a number of ways. The first is by integrating the holistic, cultural, and community-based nature of indigenous knowledge systems into university curricula and policy. This acknowledges that the educational structures inherited from colonialism are based on cultural values different from those which exist in many indigenous societies.

Eurocentricism failed to understand the holistic nature of African traditional education, particularly its community-based nature. For example, it’s argued that one of the most profound effects of western education on African traditional societies was the radical shift in the locus of power and control over learning from individuals, families, and communities to ever more centralised systems of authority. In many African indigenous societies, children learn in a variety of ways: through play or interaction with other children, immersion in nature, and by helping adults with work and communal activities. They learn by experience, experimentation, trial and error, by independent observation of nature and human behaviour, and through the community sharing of information, story, song, and ritual.

The institutionalisation of learning based on western values tainted both the freedom of the individual and their respect for the wisdom of their communities and elders. It led to the marginalisation of the role of family and community in education at all levels, including higher education. In short, its effect was to place emphasis on an individual’s success in a broader consumer culture, instead of their ability to thrive in their own environment and community. The CIKS seek to close the gap between the two.

One such approach is to incorporate the values of Ubuntu – an African philosophy that emphasises principles such as interconnectedness, compassion, tolerance, harmony, and mutual support – into the core business of the university. Although there are many definitions of Ubuntu, all point to a sense that the individual is part of a larger and more significant communal, societal, environmental, and spiritual world.

Relevant and sustainable

A key part of our work is the introduction of indigenous knowledge systems into education and training programmes, at undergraduate and postgraduate levels, to build a critical mass of human capital. This enhances the relevance and effectiveness of teaching by providing an education that speaks to students’ own inherent perspectives, experiences, language, and customs.

Crucially, it also starts to close the gap between learning and living among graduates, who are often ill-prepared to meet the development challenges of their country. By better understanding the challenges, values and attitudes of their communities, students are better equipped to make a positive and sustainable impact on society.

Finally, we work to break down the barriers between local communities and academia, industry, business, and government. This includes forming national, regional, and international partnerships with both the private and public sectors to promote the contribution of indigenous knowledge to sustainable development and to enable communities to explore the commercial viability of their products and services.

At the heart of all our work is an acknowledgement that indigenous knowledge systems and expertise exist in communities and not in academic and research institutions. These communities are the custodians of this knowledge and must be recognised as active and equal participants, and never as objects, of any research process.

Indigenous knowledge and global challenges

Embedded in indigenous knowledge systems, languages, and philosophies are potential solutions to some of the world’s most complex challenges. Our work explores how an understanding of indigenous knowledge closely intersects with the aspirations of the African Union Agenda 2063 and the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

One example is our work around climate change adaption and the role of indigenous knowledge in mitigating its impact. Indigenous knowledge systems often include cultural beliefs and practices which underline a symbiotic relationship between communities and their natural environment. Indeed, many indigenous communities have lived in harmony with their environment and utilised natural resources without impairing nature’s capacity to regenerate them.

Indigenous communities often have weather forecasting practices established through centuries of observation of their natural environments. Yet this knowledge has rarely been integrated into climate change information services. Existing weather information services, meanwhile, can lack relevance to local communities, as well as failing to acknowledge their unique understanding of local ecosystems. Our Climate Information Service Platform builds a bridge between ‘conventional’ climate information services and observations based on indigenous knowledge. It seeks to make conventional climate change information services more culturally, linguistically, and ecologically relevant and accessible – and thus more effective – while enabling knowledge to be shared.

These community-based knowledge systems, including the symbiotic and spiritual relationships between humans and the natural environment, need to be taken seriously in the design and adaptation of any climate mitigation strategies, if the latter are to succeed.

This is also a theme of our work on food security. Traditional farming, fishing, foraging and forestry are based on long-established knowledge and practices that can help to ensure biodiversity and sustain livelihoods.

In South Africa and Africa at large, smallholder farmers, the majority being rural women, depend on local knowledge systems and resources for food security, and have been able to produce food with little use of conventional practices. This again suggests that indigenous approaches need to be taken seriously in agricultural policy development, with the active participation of indigenous communities themselves. The revival and innovation of local knowledge systems may have the potential to create farmer-driven, sustainable, and biodiverse agricultural systems, regaining control of food production processes from seed to plate.

In all these ways and many more, we hope to bring about a paradigm shift towards a more democratic approach to the production, use, and sharing of knowledge: bridging the gaps between theory and practice, indigenous and ‘modern’, old and young, and living and learning.

Professor Hassan O Kaya is Director of the DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Indigenous Knowledge Systems at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

Dr Mayashree Chinsamy is Research Manager at the DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence in Indigenous Knowledge Systems at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

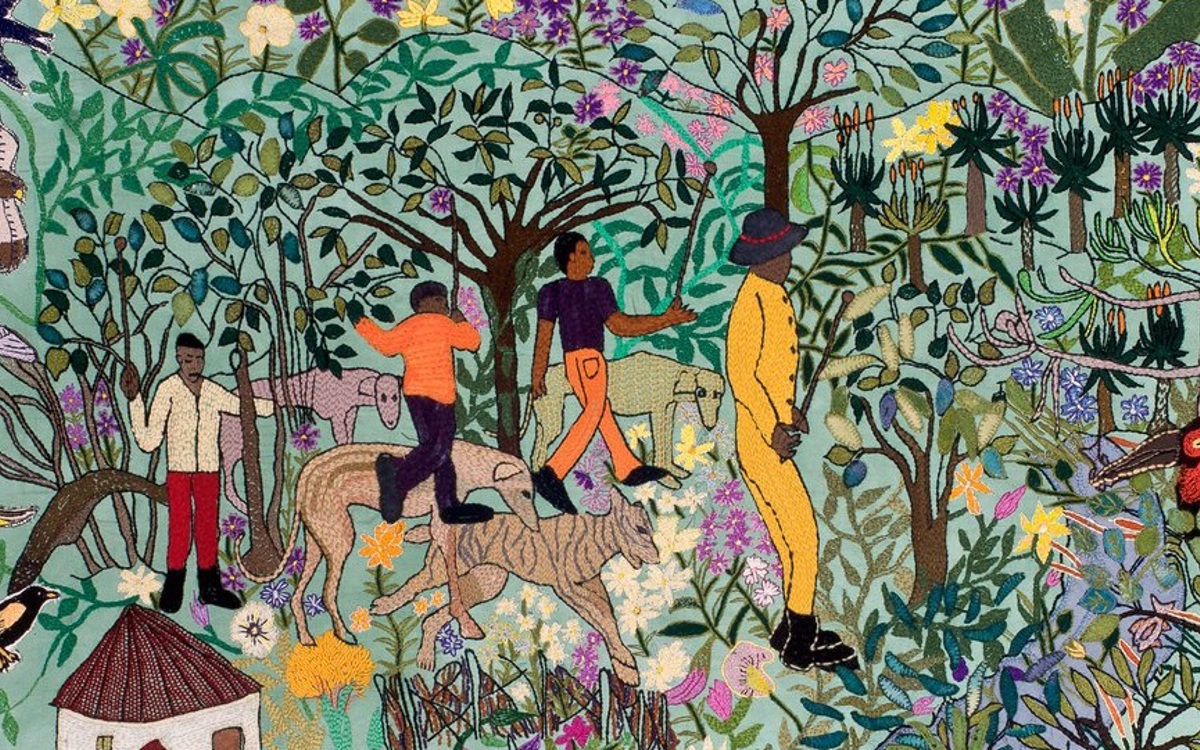

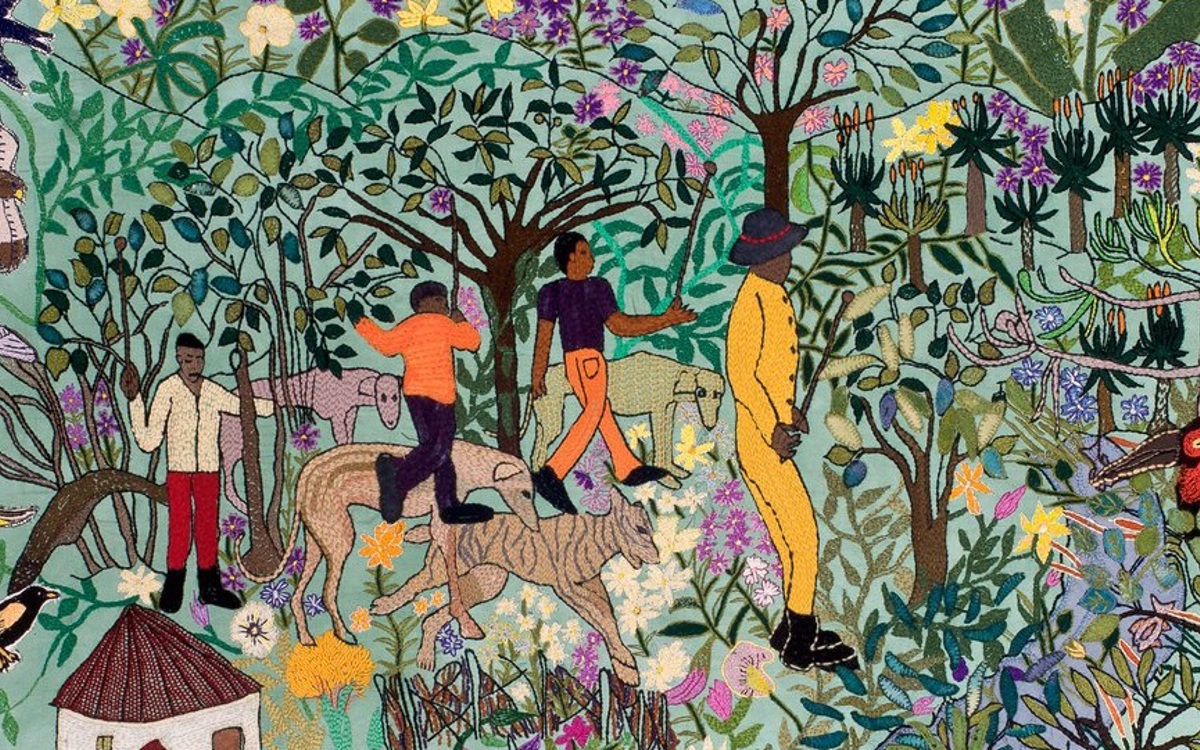

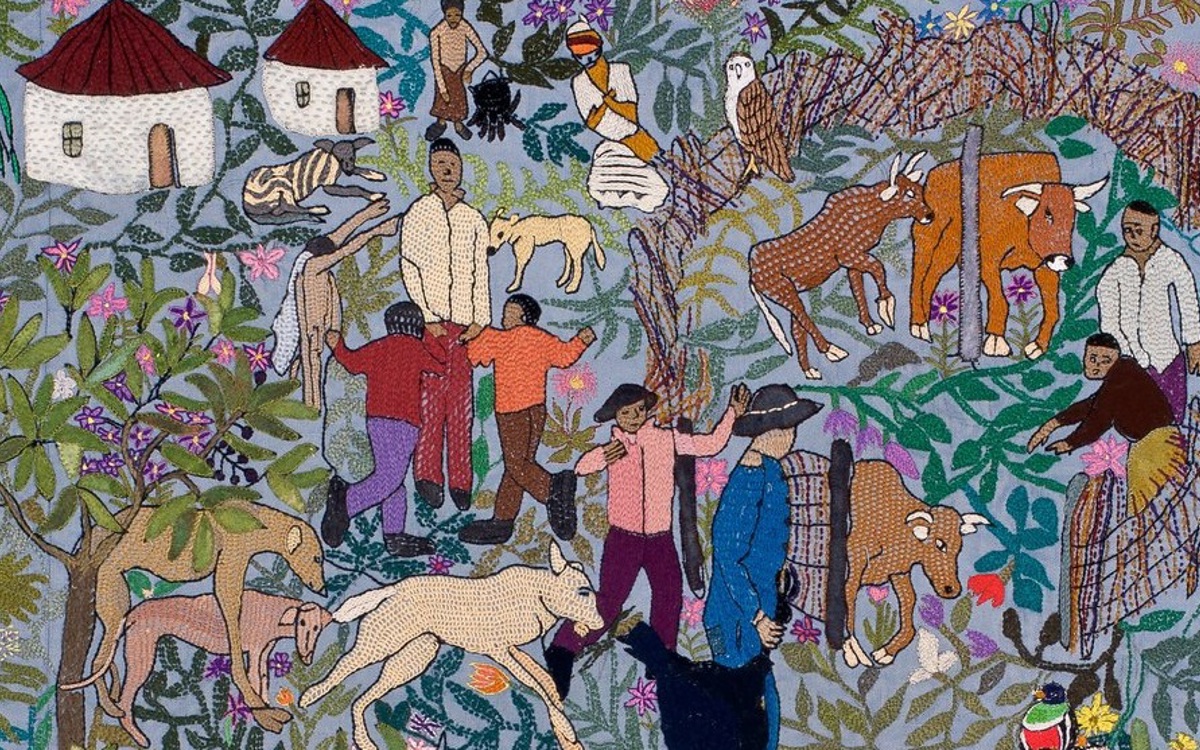

Images (from top): The tapestries are from a collection called the Intsikizi Tapestries produced by the Keiskamma Art Project in South Africa – a rural community organisation working to address poverty and disease through creative programmes and partnerships. Both are © The Keiskamma Trust. The image of smallholder farmers is © FAO/Luis Tato

The scale and urgency of today’s global challenges have never been greater, with Commonwealth countries among those most acutely affected. The ACU offers a powerful mechanism for collaborative projects, shared knowledge, and joint action, bringing universities together to tackle global challenges.