How centuries of colonial oppression have left their mark on Jamaica’s mental health. By Frederick Hickling, University of the West Indies

How centuries of colonial oppression have left their mark on Jamaica’s mental health.

By Frederick W Hickling, University of the West Indies, Jamaica

In postcolonial Jamaica, our greatest mental health challenge has been to counter the psychological impact of 500 years of European racism and colonial oppression. For the descendants of African people enslaved in Jamaica, this has been a process of dismantling the colonial policies and structures that saw thousands of Jamaicans incarcerated in lunatic asylums, while also seeking ways to heal the historical legacy of sustained structural violence and abuse that remain potent causative factors in contemporary mental illness.

The chains that bind

To comprehend the depth and complexity of this challenge demands that we consider Jamaica’s colonial history and, in particular, the sugar cane plantation system that underpinned British colonial rule. It was a system buttressed by the ideology of white supremacy and engineered through brutality and fear. Huge tracts of fertile arable land were seized by the British, and thousands of Africans ripped from their homeland to provide free forced labour. The slaves cleared the land, planted and cared for the cane, and cut and transported the crop for sugar extraction in the plantation factories – all at the end of a gun and in fear of their lives.

Enslaved people were regarded as only three-fifths human, reared for subservience and exploitation. The slave master was a cruel and vicious ruler, and collectively these murderous masters established a ruthless system of law that entrenched white supremacy through the creation of a social economy and a system of military control and punishment. This meticulously manicured system of apartheid privileged the rights of Englishmen and relegated all others to inferior status at best and ‘non-personhood’ at worst. Enslaved Africans either adapted or perished.

Many fundamental aspects of society were fashioned by this colonial apartheid system – the military, judiciary, police, prisons, education and health – including, of course, mental health. In the initial period of slavery, a slave displaying signs of severe mental illness could and would be summarily executed. Later, in 1851, an American physician called Samuel Cartwright described dysaesthesia aethiopica – a so-called mental illness affecting slaves, the ‘symptoms’ of which included disobedience, answering disrespectfully, or refusing to work.

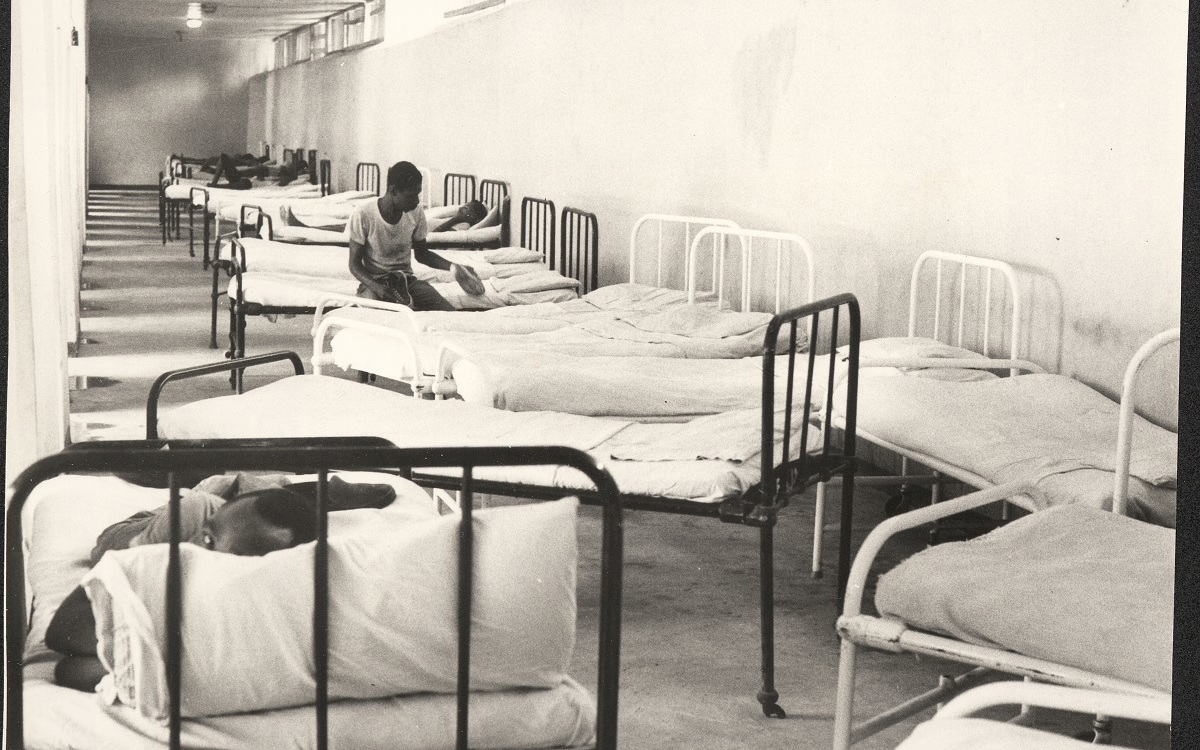

Post-emancipation, the sole care model for mentally ill Jamaicans was the Bellevue Lunatic Asylum, a vast Victorian institution built by the colonial government in 1862. Bellevue underlined and echoed the same principle of involuntary incarceration that had been a brutal hallmark of the slavery system. Among those incarcerated in desperate and deplorable conditions were political activists such as Rastafari and others displaying unusual or bizarre methods of expressing resistance to colonial apartheid. When, more than 100 years later, I found myself working as a consultant psychiatrist at Bellevue, I would learn first-hand of the depth and complexity of the mental, social and political enslavement imposed on Jamaican people. It was 1974 and Bellevue still housed 3,000 people within its walls.

The dawn of independence

Understanding the reality of postcolonial mental enslavement is extremely difficult for someone who has never lived in a colonial society. This is especially true for citizens born after the coloniser grants political independence and withdraws.

I was born in British colonial Jamaica in the dying months of the second world war, and my appreciation of the effects of British colonialism was vivid. My parents were tertiary-educated black Jamaicans, members of what was then a small intelligentsia descended from enslaved Africans. My father, a colonial civil servant, was the son of ‘free-coloureds’ from the parish of Manchester, and my mother a black concert pianist from Kingston.

My secondary schooling was at an establishment bequeathed by John Wolmer, a wealthy white British goldsmith, for the education of ‘poor whites and free coloureds’. My parental home in Kingston was ten minutes’ walk from a military base which stationed 5,000 British soldiers of the 1st Battalion of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry. I was made uncomfortably aware of British colonial racism as a teenager when I was ambushed by the white soldiers’ sons who attended my school. I escaped a beating by fleet-footing it into my home, just across the road from the parked army lorry that transported the soldiers’ children to and from school.

After centuries of struggle against British enslavement and colonialism, political independence finally came in 1962 and the process of dismantling the architecture of apartheid began. It was slow but relentless. When a commercial bank employed its first black bank teller, many Jamaicans journeyed to witness the strange sight. Thousands migrated to Britain, all on the invitation of the Empire, to help the post-war rebuilding efforts there. Rastafari was emerging as a countercultural political/religious movement that would be active in the decolonial struggle worldwide for decades to come.

But the birth of political independence also ushered in the pioneers of modern Caribbean mental healthcare, with the University of the West Indies at the helm. This cohort of indigenous psychiatrists led a revolution in psychiatric treatment; Jamaica had begun a worldwide movement against colonial custodial approaches to the treatment of mental illness.

Unchaining mental health

So, how do you decolonise a mental health system? First, we trained our own psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses. Then began a process of moving mental healthcare out of the lunatic asylum and into the community. In 1961, the University of the West Indies appointed its first professor of psychiatry, Michael Beaubrun. Professor Beaubrun taught community psychiatry in a general hospital, which was – and remains – a pioneering move: treating psychiatric patients in open wards of general hospitals lessened the stigmatisation of the mentally ill and placed them in a normal hospital environment, rather than the confines of an asylum.

These moves marked the start of vigorous strategies to downsize and dismantle Bellevue – the colonial model of treating mental illness by custody in an institution – and a shift towards community-based models of treatment. Today, Jamaica’s community mental health services provide outpatient care, crisis intervention, and outreach. GPs and community mental health officers see patients in primary care and outpatient clinics. Psychiatry has been significantly integrated into general medicine, and the stigma of mental illness has significantly declined. Crucially, community mental healthcare has replaced the traditional approach marked by involuntary certification and incarceration.

These successes, however, would unmask complex challenges for post-colonial Jamaica. Today, the legacies of slavery still reveal themselves in contemporary psychological problems: authority issues, oppressive or authoritarian sexual and social practices, and dependency issues. The uneven distribution of resources in the post-colonial era fuelled sprawling social and economic inequality and disenfranchisement, giving rise to a society where a culture of violence has become the norm. Today, Jamaica’s murder rate is nearly eight times the global average and the third highest in the world.

Dream a new world

In 2006, the University of the West Indies established the Caribbean Institute of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, offering a range of outreach services, training and interventions, but including an emphasis on cultural therapy – where creativity is used as a means of healing and as a way to explore and express painful issues. The institute is unique in Jamaica in its focus on measures to prevent, rather than cure, mental illness by looking at the risk factors and finding ways to negate them at an early stage.

Among the institute’s successes is the award-winning Dream-a-World Cultural Therapy project, which began in inner-city communities in the grip of violence and gangs. The project was initially aimed at high-risk primary school children who’d lived fragmented lives, often overshadowed by violence and hardship. These children were severely disruptive in school, underachieving academically, and at risk of facing problems in later life.

The project combines cultural therapy – using group drama, song, and dance – with remedial teaching in maths and literacy to increase self-esteem and improve academic performance. As a core part of the project, children are asked to imagine (dream) a new world on another planet. They name their imaginary world, conceive its inhabitants, and consider what they would take with them from their known world and what they would leave behind. They imagine what they would look like and what role they would play in governing their new world. Then, working with artists, the children learn to play musical instruments and compose songs, poems, and dances to bring their dream world to life.

Compared to a control group, children taking part in the project showed significant improvements in school and social behaviour and academic performance, with particular behavioural gains among boys. The project has since been rolled out to primary schools island-wide.

This creative exploration of social, personal and cultural issues is also evident in a therapeutic treatment called psychohistoriography, which my work has pioneered. This is a post-colonial model of psychoanalysis – but one specifically developed for the Caribbean and its people, rather than following a Eurocentric (e.g. Freudian) approach. It enables the exploration of issues around race, identity and culture through group discussion, storytelling, and exercises which involve challenging dominant accounts of historical events.

All these experiences remind us that it is only by recognising, confronting, and ultimately counteracting our colonial past that mental health systems can be transformed and that Jamaica can protect the wellbeing and continued survival of its people. To do this, we must continue to find approaches to mental health that are focused on inclusion and cultural expression, rather than containment and control.

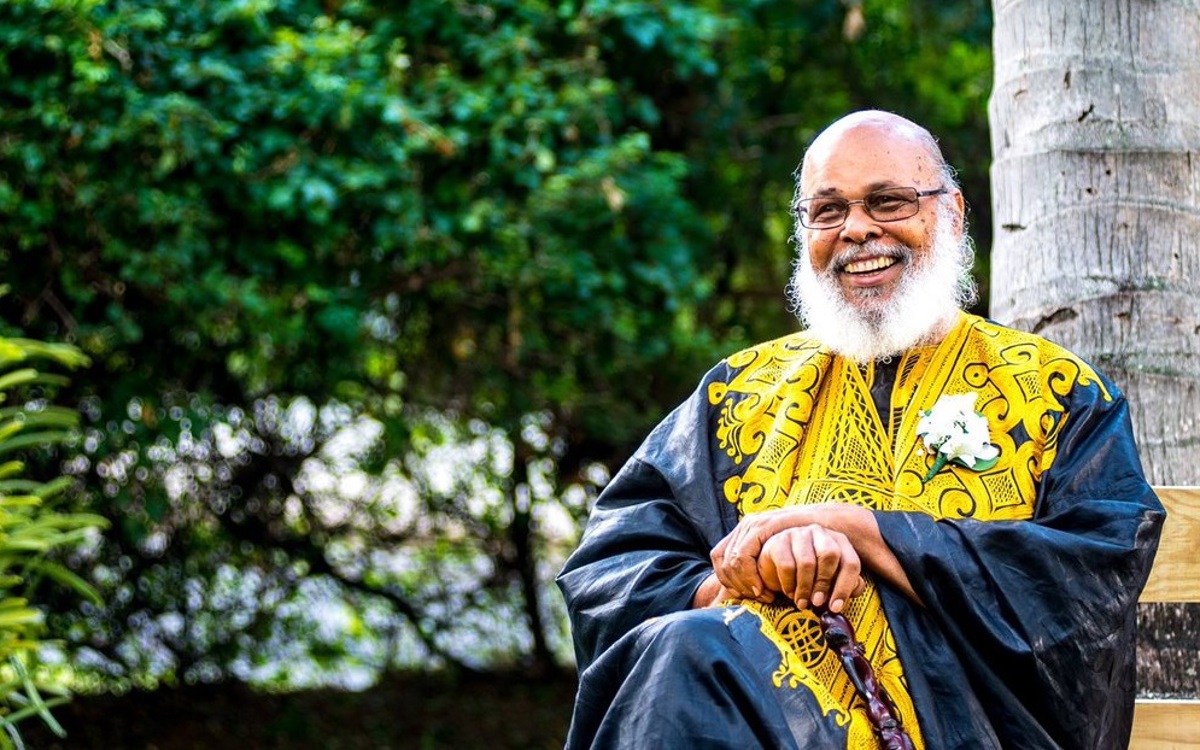

Dr Frederick W Hickling was Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry and Executive Director of the Caribbean Institute of Mental health and Substance Abuse at the University of the West Indies at Mona, Jamaica.

It was with great sadness that the ACU learned of the death of Professor Hickling on 7 May 2020 in Kingston, Jamaica, just weeks after submitting this article to The ACU Review. Professor Hickling was one of Jamaica’s most renowned psychiatrists, with Jamaican Prime Minister Andrew Holness paying tribute to him as ‘one of the preeminent voices in the field of psychiatry in Jamaica and the Caribbean’.

Professor Hickling made an indelible mark on his profession, described by international colleagues as a giant in the global movements for deinstitutionalisation, community mental health and cultural psychiatry. In 2012, he received the Order of Distinction (Commander) for his globally recognised, pioneering research work in community mental health and advocacy.

Our heartfelt condolences to his family, friends and colleagues, and we thank them for allowing us to publish this article.