What can Sri Lanka’s ancient kings tell us about protecting the natural world? By Kokila Konasinghe, University of Colombo, and Asanka Edirisinghe, General Sir John Kotelawala Defence University, Sri Lanka

What can Sri Lanka’s ancient kings tell us about protecting the natural world?

By Kokila Konasinghe, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka, and Asanka Edirisinghe, General Sir John Kotelawala Defence University, Sri Lanka

‘Let not even a drop of water flow into the ocean without being made useful for the benefit of all Earth’: this 12th century appeal for the wise use of water came from King Parakramabahu I, who ruled Sri Lanka from 1153 to 1186. While the adage is often mistranslated to mean ‘for the benefit of man’, the Sinhala word used in the original quotation – lokopakaarayen – actually means ‘for the benefit of all Earth’. This important distinction evokes a long history of environmentally-conscious decision-making in Sri Lanka, in which the interests of humans and those of nature were seen as one. But is this still true today?

Sadly, neither Sri Lanka’s beauty nor its extraordinary biodiversity have protected it from the destructive impact of human activity. Where once its forests were protected by royal decree – and those caught felling trees subject to a punishment most severe – deforestation is now one of the nation’s greatest challenges. Animals, once venerated, have seen their habitats destroyed, or found themselves chained, trained, and trafficked. Even areas protected under the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance in Sri Lanka have been leased out to private companies for development, while the water supplies spoken of so highly by King Parakramabahu I have been polluted, degraded, and depleted.

This is a surprising and unfortunate shift. From its earliest written history in the fifth century BC until the British colonial rulers seized control, Sri Lanka was a country of many kingdoms and many kings, most of whom upheld principles that would today be described as ecocentric – perceiving nature and natural objects as subjects before law, with inherent and independent rights and interests.

The stories of these ancient Sinhala kings and the high regard they paid to the natural world – often seeing nature and its components as on a par with human beings – are documented in the Mahawamsa: a historical chronicle of Ceylon – now Sri Lanka – told in Pāli, the sacred language of Buddhism. These accounts, three examples of which we recall below, remind us that ecocentric decision-making is not a novel concept, but one enshrined in the foundations of Sri Lankan legal heritage. So, what lessons can Sri Lanka’s ancient kings teach us about relating to nature?

Thou art only the guardian

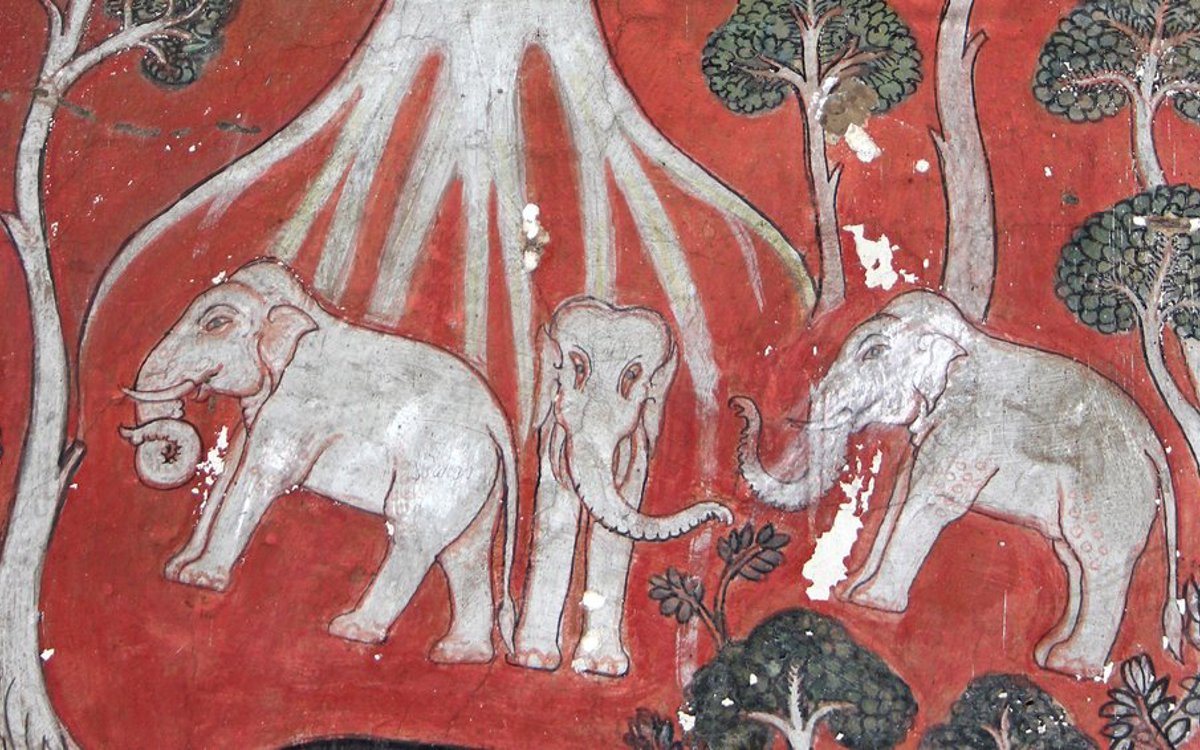

Our first example, recorded in the Mahawamsa, shows how the attitudes of ancient rulers were changed and shaped by the introduction of Buddhism to Sri Lanka in the third century BC. In this particular story, Devanampiya Tissa, one of Sri Lanka’s earliest kings, was on a hunting trip when he encountered Arahat Mahinda thero, a Buddhist monk and missionary. Seeing that the king was in pursuit of a deer, Arahat Mahinda thero preached to him: ‘O great King, the birds of the air and the beasts have as equal a right to live and move about in any part of the land as thou. The land belongs to the people and all living beings; thou art only the guardian of it.’

As the story goes, the king dropped his bow and arrows, renounced hunting, and became a follower of Buddhism. Later he would declare the Mihintale area a sanctuary for animals – arguably creating the world’s first ever wildlife sanctuary.

This sermon on the rights and freedom of beasts and birds later found its place in one of the most celebrated and significant rulings in environmental law at the International Court of Justice: the Gabcíkovo-Nagymaros (Hungary v Slovakia) Project Case. It was during this lengthy dispute over the construction of dams in the Danube river that the International Court of Justice considered the principle of sustainable development for the first time.

In his comments, the honourable judge Weeramantry noted that the sermon contained within it the first principle of modern environmental law: the principle of trusteeship of the Earth’s resources. He went on to highlight the relevance of Buddhist thought and practice to our actions towards the environment: ‘The notion of not causing harm to others and hence sic utere tuo ut alienum non laedus (a legal maxim meaning ‘use your own property in such a manner as not to injure that of another’) was a central notion of Buddhism,’ he wrote, and one that translated well into environmental attitudes. The notion of not causing harm to others, he explained, was extended by Buddhism to include future generations and ‘other elements of the natural order beyond man himself’.

All beings deserve justice

Our second example is courtesy of King Elara, who ruled the country from 204 to 164 BC. According to the Mahavamsa, the king had a bell hung above his bedhead with a long rope hanging out of the window. Any of the king’s subjects who wished to complain of an injustice could ring it. But the king’s commitment to justice was put to its toughest test when a chariot driven by his own son ran over and killed a calf. The mother cow, grief-stricken at the loss of her beloved child, rang the king’s bell pleading justice for her son.

The king’s response, as told in the Mahavamsa, unequivocally establishes that he saw no difference in value between a human life and that of an animal. He ordered his reckless son to be executed in the same manner in which the calf had died, and underwent the same suffering, loss and pain as had the mother cow.

Although King Elara’s response was extreme, so perhaps is the absence of compassion shown to animals in the modern administration of justice. A recent example is provided by a magistrate court in Colombo who issued a court order allowing the return of a number of baby elephants not to their mothers but to their captors – the very people assumed to have killed the mother elephants.

Have benevolence for all (even those that bite)

King Buddhadasa reigned from AD341 to 370 and is renowned not only as a king but for his excellence in medicine, surgery, and veterinary sciences – extremely impressive for a fourth century king. The Mahawamsa tells how the king’s kindness extended to all living creatures, describing his love and compassion towards the animals as ‘that of a father towards his sons’. Like King Elara, this was tested one day when the king encountered a snake laid out on an anthill, apparently suffering from acute pain. The king reached out to the snake and gently asked him not to be ‘inclined to bite him in thy sudden attacks of rage’. Hearing this, the snake thrust his head into a hole to ensure he would not inflict any harm on the king. The king – who was as skilled as he was benevolent – performed surgery on the snake and cured him, after which the grateful snake gifted him with a precious gem.

It is believed that King Buddhadasa also established botanical parks in which to grow valuable, medicinal plants. One of these – the Nilgala forest reserve – remains today. But even this last remaining legacy of a great king has recently fallen victim to land-grabs and deforestation in pursuit of the commercial yields of rubber, plantains, and sugarcane.

Our fellow brethren

It is not certain when exactly Sri Lankan rulers began to deviate from the ecocentric paths of their ancestors. It might be due to colonialism, to open markets and capitalist influence, or to short-sighted, self-centred rulers led by their own political and economic agendas. Perhaps it’s a combination of all these.

Whatever the reason, Sri Lanka is rapidly losing sight of the ancient wisdom of treating the environment, animals, and plants as fellow brethren of humanity. Environmental decision-making in the country now perceives nature as a mere object that can be polluted, destroyed, and ripped off, and that exists solely for the benefit of humans. If Sri Lanka is to protect, conserve and preserve the last bits of its natural heritage, now is the time for Sri Lankan leaders to move away from extreme anthropocentrism and to re-embrace the ecocentrism that is so much a part of our nation’s heritage. Thousands of environmental disasters throughout history have taught us one great lesson: there is only one way for survival and that is to work together with nature, not against it.

Dr Kokila Konasinghe is a Senior Lecturer and founding Director of the Centre for Environmental Law and Policy at the University of Colombo, Sri Lanka. Kokila is also member of the Commonwealth Futures Climate Research Cohort – a joint ACU and British Council initiative that supports rising-star researchers from around the world to bring local knowledge to a global stage.

Asanka Edirisinghe is a Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Law at General Sir John Kotelawala Defence University, Sri Lanka.

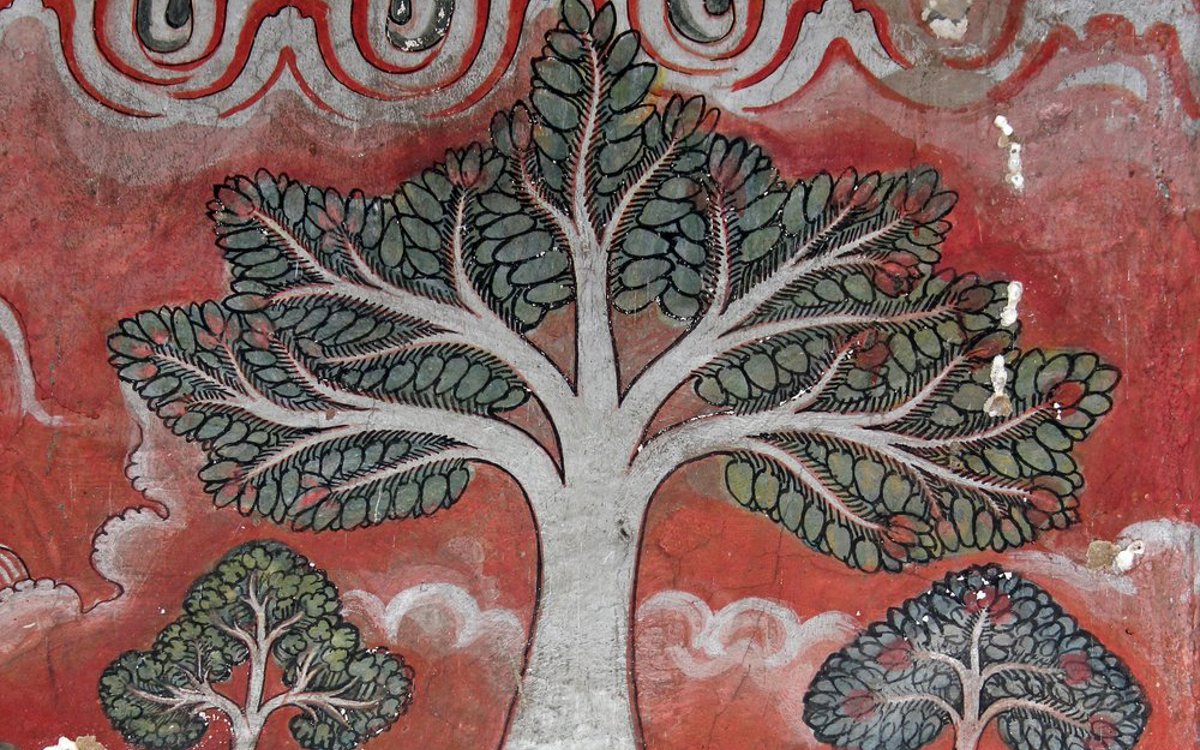

Images 1 and 3 are from a painting of the the sacred Bo tree in the Golden Temple of Dambulla, photographed by Sabena Jane Blackbird at Alamy. The Kandyan painting of King Devanampiyatissa in Mihintale was photographed by Suresh Vasant for ephotocorp at Alamy

Catch up now, including 'The wisdom of ages' - how indigenous knowledge can help us to think critically and consciously about the world around us.