Understanding Africa’s complex history is part of reclaiming a past mediated through European interpretation. By Nana Yaw Boampong Sapong, University of Ghana

In the 1990s, two freshly enrolled students walked onto the University of Ghana’s Legon campus, eager to take the next decisive step to responsible adulthood. Hopefully, after completion, there will be decent jobs waiting, opportunities to start families, and to travel the world. However, amidst this hope and optimism, they also stepped foot on campus not knowing what to expect. One of them was a shy, bright-eyed freshman, whose admission letter stated that his subject combination was English, history and philosophy – a fine ensemble. Unfortunately, his pride took a beating when a classmate asked lugubriously: ‘What are you going to do with that?’

Decades later, that classmate’s footsteps no longer echo in the halls of Legon, but his question remains. Often, I hear people question the value of these subjects and the humanities in general. In a market-driven world and a knowledge-based economy, it’s clear that higher education has moved away from being a public good. It is no longer education for its own sake, but education tailored for a perceived market niche. Meanwhile, as leaders and policymakers scramble for solutions to the intractable problems of the 21st century, humanities are often sidelined in conversations on how to achieve peace and prosperity for all.

As a historian, I believe this is a serious oversight. Africa’s history is complex and intricate and, as Stephen Ellis concludes in Season of Rains, it is an awareness of this complexity that equips us ‘to understand Africa’s place in a fast-changing world and to read accurately the omens concerning what may happen in the foreseeable future’. And I’d like to start with the history of my own institution and what it tells us about a shifting world.

Transition and transformation

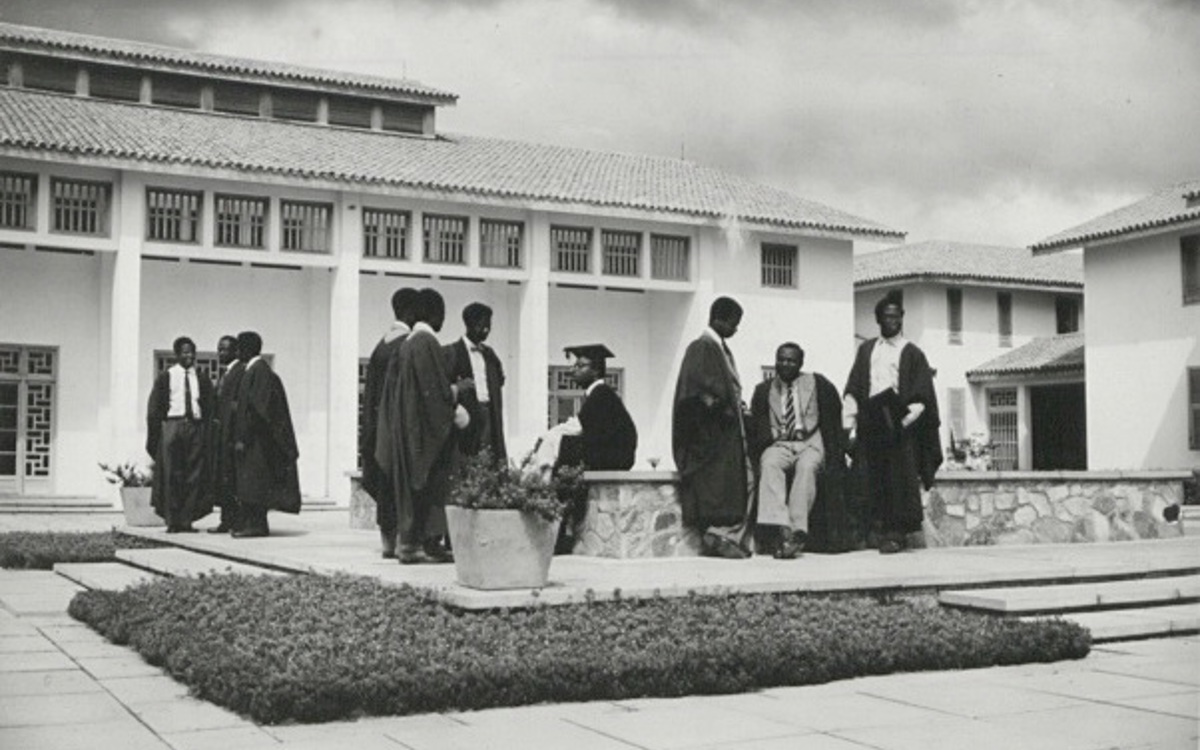

The University of Ghana first opened its doors in 1948 as the ‘University College of the Gold Coast’ after much manoeuvring by African and colonial officials. These officials agreed that universities were a pathway to individual and national development, but for political expediency disagreed on location and number. In the end, it was agreed that Ghana’s Gold Coast should have its own university, separate from one to be founded in Nigeria. Reflecting this colonial heritage, our campus today still maintains architecture that evokes of the idea of empire and the blending of east and west.

A list of the university’s founding departments from 1948 is instructive and suggests an intended synergy between the humanities and the sciences. These founding disciplines included history, classics, English, mathematics, economics, geography, physics, chemistry, botany and zoology.

In the ‘golden years’ of the university (the 1950s and 60s), when the focus was on social change, the humanities thrived. But by the 1970s, Ghana’s ailing political economy, characterised by financial cuts, brain drain, and student unrest, ushered the university into an era of crisis, triggering demand for the humanities to rationalise their existence. The mid-1990s saw a period of recovery and ‘transformation’, as US foundations such as the Partnership for Higher Education in Africa (Carnegie Corporation, the Ford, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur, and Rockefeller Foundations) and international finance (World Bank, European Union) invested millions in African universities. The belief was that African universities such as the University of Ghana could ‘transform’ themselves and stimulate national development. This, however, did not save the humanities from needing to justifying their existence. Although the executioner stayed his hand, the guillotine was not dismantled.

Today, universities in Africa continue to innovate and reform, but this process is often based on the recommendations and prescriptions of international donors who continue to provide grants. In 2014, the University of Ghana launched an ambitious strategic plan to become a world-class university, with nine strategic priorities, including research, teaching and learning, and gender and diversity. In the following year, the United Nations, filled with foreboding of an impending global calamity, authored the Agenda for Sustainable Development, with 17 goals including an end to poverty and hunger, as well as good health and wellbeing, quality education, reduced equality, peace and more – all goals that suggest a strong need for input from African universities, and particularly their humanities’ departments. So, where does history come into it?

The lucid moment

We all have that ever-present relative in our families. Quiet, observant, ubiquitous, present at every crucial celebratory stage in the cycle of life. No one quite agrees on her current relevance, but she is always there. No one can tell how old she is because she outlived all her contemporaries. In our imaginaries, she was there when it all began. She is immortal. She provides that lucid moment. She is History.

History is by default analytical. It provides an intellectual space where one can interrogate errors, think of possibilities, and nurture dreams of a different future. Our sense of urgency, agency, purpose, and possibility, which have time and again brought watershed moments in science, technology, engineering and medicine, have been fuelled by history, historical anecdotes, and narratives of gritty lives and indomitable societies.

Since gaining independence from colonial rule, history departments in universities across Africa have staked out their claims, reclaiming a past that had been mediated through European interpretation. At the University of Ghana, we consider Africa’s history and development to be a coat of many colours.

Each semester, I teach a course on the history of Africa and its interaction with the wider world. Through instances of encounter such as commercial or religious activities, we tease out illustrations of negotiation, adaptation, change, and continuity. We learn to think ‘Africa’ by redefining the African past through the lens of Africans. We learn to think ‘global’ by recognising the intersecting relationships between different parts of the continent, and how global interactions have shaped it. Finally, we think ‘history’ by learning to frame and explain historical change and continuity. It is hoped that at the end of the course, students can cogently narrate an African past within which Africans were active agents, not hapless victims, villains, or the vanquished.

This understanding of agency is important because the colonial era is often felt to have an entrenched, hegemonic hold over the direction and focus of historical research. Moreover, many themes found in our history, especially conversations emanating from the denouement of Atlantic slavery, the consolidation of capitalism and Empire, and the negotiation of social relations, offer a deeper understanding of the issues confronting the postcolonial state and cast a valuable light on present-day problems.

The will to survive

Our world is still an object of anxieties. But through the sands of time, we have carried stories of challenges, perseverance, and triumph; narratives borne out of the human will to survive and to overcome. Informed by this will and the lessons of history, the UN set the SDGs. It is the same will and history which compelled the government of Ghana to adapt the SDGs to the local context. It is also this will and the lessons of history which obliged the University of Ghana to have a strategic plan and, today, compels this historian to tell all not to forget the humanities. Our very survival may depend on it.

Dr Nana Yaw Boampong Sapong is Senior Lecturer of History at the University of Ghana, a poet and novelist, and editor of the journal Ghana Studies.

Image: Photograph of students outside the University College of the Gold Coast (now the University of Ghana) in January 1957, courtesy of the UK National Archives, ref CO 1069-46-19.

All written content published by The ACU Review is copyright of the Association of Commonwealth Universities or the contributing author/s, and may not be reproduced without written permission from the Association of Commonwealth Universities. Please contact [email protected] with enquiries.