How historical forces have shaped the way medicine is taught, practiced, and experienced. By Sarah Wong and Amali Lokugamage, University College London, UK

Universities need to engage with the historical forces that have shaped the way medicine is taught, practiced, and experienced.

By Sarah Wong and Amali Lokugamage, University College London, UK

Medical schools play an important role in shaping the doctors of tomorrow – not only their knowledge and skills, but the social and cultural assumptions that underpin their practice. Through their curricula, medical schools often aim to produce a certain type of doctor: one who aligns with professional expectations and who preserves and upholds established norms. A decolonial approach to medical education, however, calls for the training of doctors who are willing to challenge this status quo, armed with a deep understanding of the historical, social, cultural, structural and political determinants of health, and the ability to think critically about the questions that matter most.

The shape of the world as we know it today has been carved from its crust by the course, currents, and ripples of colonialism. Transcending historical events, colonial influences persist in the imbalances of power and privilege that confront us every day, and are integrated into the very systems that structure our everyday lives – including healthcare. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has cast a spotlight on disparities in healthcare infrastructure and resources, revealing underlying structural determinants of health that have led to higher mortality rates among historically disempowered groups. This is a damning reminder that colonial-era forces such as racism are not obsolete but have simply taken on more insidious forms.

Wherever the colonial narrative remains our predominant mode of understanding the world, adopting a decolonial lens entails a paradigm shift: a subversion of hierarchies, an overturning of common knowledge (or rather, perpetuated assumptions), and a decentring of a singular narrative of what it means to be human, with particular attention to the margins.

Asymmetries of power

In a disciplinary field often characterised by conservatism and Eurocentrism, it is perhaps unsurprising that medical schools have been particularly resistant to decolonisation. In much of the Commonwealth, western biomedicine is venerated as a gold standard for medical practice – a bias illustrated by the interchangeable use of ‘western’ with terms such as ‘evidence-based’, ‘scientific’, ‘mainstream’ or ‘conventional’. Indigenous and traditional medicines are disregarded by many medical practitioners as superstitious and unfounded.

This has led to the displacement of diverse understandings of health and illness, ignorance of the contributions of non-western healing systems to a global repository of knowledge, and discrimination against aspects of medicine that do not fit neatly within the biomedical framework.

As in the colonial era, medicine remains a highly hierarchical field. While there has been a general shift away from medical paternalism (in which the doctor is deemed a superior and ‘father-like’ authority figure, who may disregard a patient’s wishes or choices), these attitudes remain deeply entrenched in medical cultures in Britain and in various ex-colonial countries. The resulting doctor-patient relationship is characterised by an asymmetry of power that mirrors that between the colonists and the colonised.

Towards a critically conscious curriculum

So, how can medical schools help to undo the impact of colonial legacies on healthcare? While any endeavour to decolonise education requires extensive institutional reform beyond simply what is taught, reviewing the curriculum is nonetheless a chance to explore the inequalities, assumptions, and unconscious biases that may be embedded within its teaching.

In our roles as a final year medical student and clinical educator at University College London Medical School, and as members of ex-colonial countries ourselves, we recognise the absolute necessity of a decolonial lens in ensuring equitable access to healthcare for the most disempowered groups in our society. Through the school's Decolonising the Medical Curriculum initiative, our staff-student working group has worked collaboratively to develop teaching sessions that aim to be more historically, culturally, and critically conscious.

These teaching sessions fall within the Clinical and Professional Practice module, which runs throughout the six-year medical degree and aims to instil empathy, integrity, and professionalism among students. The module, which covers areas such as communication skills, ethics, and the social determinants of health, now enables students to explore areas of the medical curriculum where decolonial perspectives have been excluded and suppressed.

Beyond boundaries

The first such area is the conceptualisation of race and culture within medicine. Science has revealed a greater degree of genetic variation between individuals belonging to the same racial group than between different races. The persistent way in which populations are still stratified by race begs the question of what we actually talk about when we talk about race: if race is a social construct, what are the political, historical and cultural factors that delineate its boundaries? And what are the consequences of its usage as a proxy term for cultural difference, papering over deeper social divides?

The lack of substantiation for a biological basis for race has not deterred its inclusion in medical discourse, whether as a variable in clinical algorithms or a risk factor for an array of conditions. Aside from its role in confounding the association between discrete genetic markers and specific medical conditions, the racialisation of medicine distracts from the structural determinants of health that produce health inequalities.

If medical students are not exposed to critical perspectives around race and ethnicity, the danger is that medical schools will serve to reinforce the false (and generally racist) notion that these are inviolable categories that exist in nature.

From stereotyping to self-awareness

The way that culture is traditionally framed in medicine has led to the stereotyping and ‘othering’ of minority ethnic individuals. The ‘cultural competency’ model, which seeks to equip medical students with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to handle cross-cultural encounters in clinical practice, has become a mainstay of medical curricula. While there is value in cultural awareness, the cultural competency model may promote a simplistic understanding of what culture entails, disregarding the nuances of what it means to belong to a culture – and, indeed, multiple cultures – as an individual in the world.

Its focus is primarily on the culture of the patient, rather than that of the clinician and the healthcare environments they inhabit. The patient is the one represented as exotic or unusual, while the medical establishment and its members are, by default, assumed ‘acultural’.

Given the crucial role that unconscious biases play in shaping our behaviour, the importance of self-awareness in mitigating discrimination cannot be overstated. One approach that accounts for these systemic biases in healthcare is the ‘cultural safety’ model developed in Australia and New Zealand. This model recognises the broader political and historical factors that lead to poorer health outcomes for indigenous groups, and emphasises reflexivity – an examination of one’s own beliefs, biases and judgements – in the clinical encounter.

Faith in the system

Colonial influences are also found in the ways in which medical knowledge is produced, valued, and judged. The advent of more rigorous regulations and guidelines around clinical research has heralded a new era of evidence-based medicine. Critics suggest that this has led to complacency among medical professionals in the form of unquestioning faith in the system. This is despite the fact that further analysis of clinical recommendations released by medical institutions have often revealed a surprisingly weak evidence base behind each guideline and a lack of transparency surrounding it (e.g. by not publicly displaying evidence grades in national guidelines).

As a field funded by powerful institutions and fuelled by institutional interests, the room for bias in medical research, in spite of regulations, cannot be overlooked. An orientation in global health reveals a stark geographic bias in research output between lower and higher income countries. This trend is dependent on a number of factors, including the higher levels of funding allocated to research conducted by westernised institutions for higher-income populations, the preferential publication of such research in the most influential journals, and the prioritisation of quantitative research over qualitative methods which are often more feasible in low-resource settings.

Medical students should be taught to remain sceptical – not with the view to undermining public trust in medical institutions, but in fact to strengthen it by questioning established knowledge and thinking critically about the broader ways in which knowledge is constituted.

Curiosity and humility

Medical pluralism refers to the coexistence of differing medical traditions, beliefs, and practices, and may be another useful area for medical students to explore. When caring for culturally diverse populations, knowledge of – and respect – for different systems of thought around healing promotes trust within the patient-doctor relationship. This trust has been shown to improve patient engagement with healthcare services and, ultimately, health outcomes.

The western approach to illness and health operates within a positivist framework – in which the only ‘valid’ or acceptable knowledge is that produced through scientific interpretation of data or evidence. Within this framework, illness is understood as a disease entity, rather than an individual and personal experience of affliction.

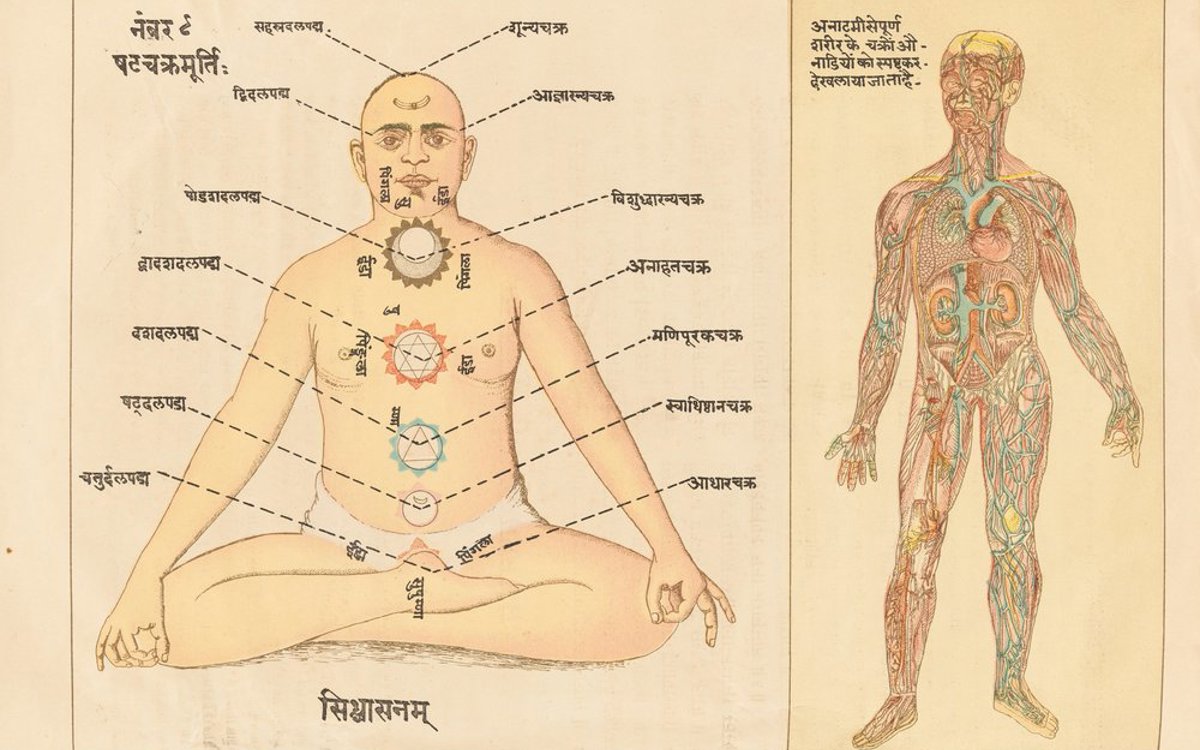

A model of healthcare that is truly ‘holistic’– or, in other words, treats the patient as a whole person – is based on the integration of multiple perspectives of what constitutes health, including the patient’s own. Such holistic and integrated approaches form the basis of many complementary and traditional medicines, alongside an inclination towards personalised care that accounts for the psychosocial (and spiritual) factors that contribute to wellbeing. Although medical students will become members of predominantly biomedical institutions, a decolonised medical curriculum can help to cultivate intellectual openness, curiosity, and humility towards other approaches to healing.

Ultimately, the radical reform that decolonisation calls for requires platforming of voices that have historically been marginalised, oppressed, and silenced. This requires attention to person-centred perspectives, public engagement, and the co-production of healthcare research alongside service users, particularly representatives from the most marginalised sectors of society. It is time to engage with the histories that have shaped the way medicine is taught, practiced, and experienced in our world today, and broaden our gaze to old and new narratives about what healing entails.

Sarah Wong is a final year medical student at University College London Medical School, UK. She is a Chinese Singaporean of mainly Hakka descent, with ancestral roots across Malaysia and in Peranakan culture.

Dr Amali Lokugamage is a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist, and Honorary Associate Professor at University College London Medical School, UK. She was born in Sri Lanka and studied in the UK.

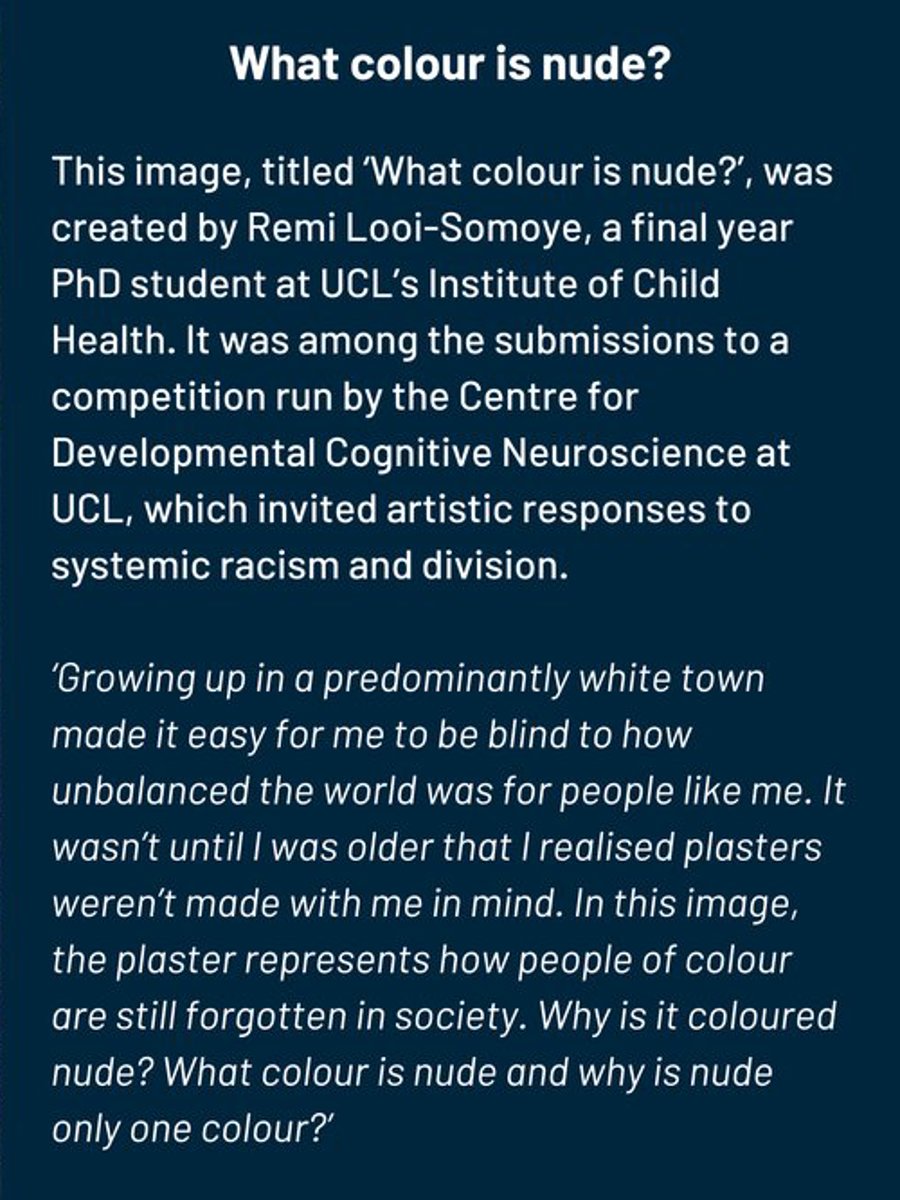

The photograph, 'What colour is nude?’ , is by Remi Looi-Somoye and was among the submissions to a competition run by the Centre for Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience at UCL, which invited artistic responses to systemic racism and division. Visit www.cdcnart.co.uk to find out more or view the entries. Other images (from top): silhouettes by Melitas at Shutterstock. 'White coats for black lives' protest by Maria Khrenova/TASS/Alamy Live News. Yogic illustration courtesy of the Wellcome Collection, licensed under CC BY 4.0

Catch up now, including 'Enslaved minds: decolonising mental health' by the late Dr Frederick Hickling