How one university is teaching its students how to be happier – and it counts towards their degrees. By Bruce Hood, University of Bristol, UK

The University of Bristol is teaching its students how to be happier – and it counts towards their degrees.

By Bruce Hood, University of Bristol, UK

Everyone seems to be talking about student mental wellbeing these days. A recent study by the Insight Network and Dig-In found that almost half of UK students have experienced a serious psychological issue for which they felt they needed professional help. These high levels are consistent with reports from both Canada and the US, where one nationally representative survey found that more than half of US college students reported feeling hopeless, and over 60% were experiencing overwhelming anxiety.

It has long been recognised that the transition to university can be challenging. Indeed, one of my first scientific papers published over 30 years ago was on homesickness in first-year students. But today, the problem of student mental health is crippling the process of higher education at its core. As lecturers, we should be teaching and inspiring our students about our specialist topics; instead, we are spending more and more of our time dealing with students who are unable to cope.

What makes this more tragic is that these students are at a time in their lives when they should be enjoying the freedom of independence and blossoming into adulthood – discovering who they are and what a fascinating world higher education can be. Instead, many are anxious or depressed and, at the extreme end, some have taken their own lives.

Three years ago, the University of Bristol experienced a spike in student suicides which immediately drew press attention. It’s not that universities are toxic environments as the negative press suggested – in fact, there is no difference between the numbers in higher education compared to the general public. Rather, suicide, as well as self-harm, has been on the rise for all young people in the UK since 2009; the numbers in higher education simply reflect this tragic trend.

Stigma and seeking help

One problem in universities is that students are not always seeking help. Although UK universities have seen sharp rises in students accessing support services in recent years, only 5% currently receive treatment either in campus counselling programmes or off-site. A recent study of college students in the US suggested that up to 84% of those in need of mental health services do not receive them.

So why aren’t students seeking the help they need? Some may not do so because of the stigma associated with mental health. This concern is particularly problematic for international students from cultures that do not recognise, or are less sympathetic to, those suffering from poor mental health, regarding it as a sign of weakness. Many students also choose not to discuss mental health problems with faculty members, and tutors in particular, because they don’t want such problems to appear on their records or, as students put it: ‘I wouldn’t want it on my CV’.

This dire situation has led to increasing despair among academic staff, which in turn is starting to impact on their own mental health. So I was intrigued to hear that a former student of mine, Laurie Santos – now a leading academic and head of one of Yale University’s residential colleges – had introduced a course at Yale called ‘Psychology and the Good Life’, teaching a set of scientifically‐validated strategies for living a more satisfying life, based on the field of positive psychology. It quickly became Yale’s most popular class ever, with one in four students signing up to learn how to increase their happiness and build more productive habits. But could something similar work here at Bristol?

Lifting the barriers

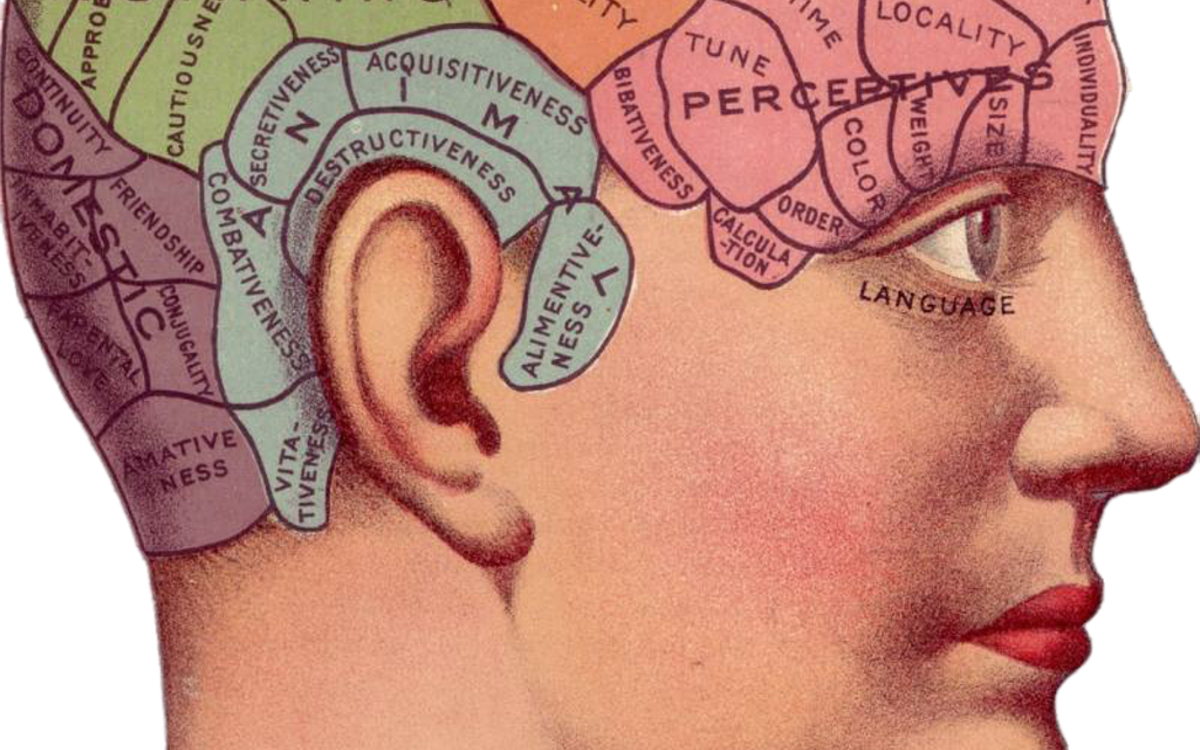

Inspired by Laurie’s success, and keeping in mind the barriers that prevent students from seeking help, I developed ‘The Science of Happiness’ – a university lecture course that draws from fields as diverse as philosophy, psychology, economics, statistics, and neuroscience. I wanted to approach the topic from a critical viewpoint, rather than as an evangelist for self-help, because I think the field has become saturated with pseudoscience and bold claims. Also, approaching the topic as a science removes many of the sceptical barriers that highly educated students might have, as well as legitimising the topic for students from cultures where poor mental health is deemed a weakness.

At first, I was daunted. Mental health is not my primary area of expertise (I usually study cognitive development), but I soon realised that there was a vast volume of research from the field of positive psychology that claimed you could improve mental wellbeing with simple regular activities and routines. It seemed too good to be true, but if I could make the course engaging enough, then, at the very least, maybe a handful of students would learn something about psychology and seek out services if they needed them. As Richard Layard, the influential ‘happiness economist’ has advocated: ‘Schools and universities need to create an atmosphere where mental health problems can be freely discussed. And they need to know how to refer students for professional help (preferably within their own institution).’ A course in the science of happiness seemed to be the obvious way to promote such an atmosphere.

Mindbugs and misconceptions

The course begins with a look at common misconceptions about happiness and how it is generated. For example, most think that the path to happiness lies in success in education, a good job, a high salary, and the acquisition of material possessions. Although these goals can certainly contribute to happiness, they are not, in themselves, a guarantee and bring no way near the levels of satisfaction one anticipates. In fact, we quickly get used to things, leading to the so-called ‘hedonic treadmill’ where we are constantly chasing the next big goal that we never really reach. The course explores other common flaws in the human mind, using examples from perception and cognitive psychology to demonstrate how the human mind is infested with so-called ‘mindbugs’ – distortions in an otherwise efficient system. It explains why we are a species that is constantly comparing ourselves unfavourably with others.

Ultimately, the secret to happiness is changing the way you think about your goals in life. A course can be illuminating, but changing mindsets and behaviours is easier said than done. Therefore, in addition to lectures, the course has a significant component of ‘happiness homework’ – activities based on positive psychology principles – to see if students can improve their own mental wellbeing.

The first run of the course was a huge success, drawing in over 400 students as well as staff from across the university. We administered self-reporting measures of mental wellbeing, before and after the course, and found significant improvement. But maybe we were already preaching to the choir. Maybe this voluntary course attracted individuals who were already experiencing mental health issues and expected to improve. Would it work for other groups?

Raised eyebrows and happiness hacks

In 2019, we turned ‘The Science of Happiness’ into a credit-bearing unit for all first-year students from any discipline. But unlike most other courses, there were no graded exams. This raised many eyebrows among colleagues who have become so entrenched in the examination mindset that they find it incomprehensible to award credit without one. But, as I pointed out, mental health issues can be linked to exam stress, so it would have been inconsistent to have a graded exam associated with the course. Instead, credit was to be awarded on the basis of engagement – something that actually requires more effort from the student.

We were sure that the prospect of an interesting topic, combined with no graded examinations for credit, would be considered an easy option. But what students had not anticipated was the level of commitment which, for some, proved more challenging than cramming for a final exam.

Each week, in addition to lectures, students meet in small groups (‘happiness hubs’) mentored by senior students, where they have to engage in a programme of activities (‘happiness hacks’) designed around the course, as well as a final group project. They also have to undertake their own self-assessment and are expected to journal their activities. Attendance is monitored and the importance of commitment and structure in one’s life is emphasised.

Each ‘happiness hub’ is a mixture of students from different disciplines, backgrounds, and often attitudes, but they have to get on. The groups are challenging, but then so is life. And the course is radical in some other ways too: no laptops or smartphones are allowed during lectures, and recordings are only viewable on request, in order to address the problem of low attendance that is ubiquitous for recorded lectures. Everything is designed for maximum engagement over 12 weeks. But did it work?

Happy findings

At the risk of compromising future academic publication, and our analysis is still ongoing, I can say that our initial investigations into student mental wellbeing showed highly significant effects for students taking the course, compared to those waiting to take it. What’s so encouraging about this finding is that their change in happiness was not predicted by the extent to which they thought mental wellbeing was a priority. This is a really important point, because many studies have demonstrated that people who engage in positive psychology interventions have a strong expectancy that they will work. While we know that some students took our course because they were motivated to improve their own mental states, many others signed up because they were genuinely interested.

Most importantly, and another reason why ‘The Science of Happiness’ is so valuable, is that students who took it were less likely to drop out of graded exams on their other courses. In our lectures, we talk about fear of failure and why it is so important to keep challenging ourselves. Maybe this message made a difference on their other courses as well.

I think we need to create the sort of atmosphere that returns us to a time when being at university was considered one of the best times of one’s life. What remains to be seen, however, is whether the positive effects of ‘The Science of Happiness’ last, as students progress to harder, more challenging senior years at university. To answer that, we need to treat this course like a true experiment, taking place over time. This is why we will continue to review and revise the course to ensure that our approach, as well the content, is rooted in science.

As this article went to press, the world has been turned upside down with the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. No one is certain when things will return to normal and the need for a course on happiness is more important than ever. In response, we are now delivering ‘The Science of Happiness’ lectures online through video conferencing technology, and the ‘happiness hubs’ are meeting in virtual space. Remarkably, this type of video interaction seems to have brought students and mentors closer together. Next autumn, we will be delivering the virtual course at Cardiff University, as well as exporting it to other interested universities. Whether in real life or virtual classes, however, the central message remains the same: you may not be able to control all the events around you, but you can control the way you respond to them.

Professor Bruce Hood is Director of the Bristol Cognitive Development Centre and Professor of Developmental Psychology in Society at the University of Bristol, UK.

Images (from top) Oberholster Venita at Pixabay. Image of Laurie Santos courtesy of Yale University