Could teaching about ‘the environment’ actually be at odds with protecting nature? By Tom Oliver, University of Reading, UK

Could teaching about ‘the environment’ actually be at odds with protecting nature?

By Tom Oliver, University of Reading, UK

What does the word ‘nature’ mean to you? For many it conjures visions of wild places away from the hustle and bustle of people. For me, it evokes the sun’s slanting rays across forested landscapes, of dappled light through woodland canopies. The meaning of ‘nature’ has changed since its first use. Derived from the Latin natura, literally meaning ‘birth’, it used to refer to the innate qualities or essential disposition of something. But over time, it began increasingly to describe to something ‘out there’ and separate to humans, rather than some essence within.

In the 1960s, the word ‘environment’ began to take over, derived from the French environs – explicitly describing something surrounding us. Its increasing use in our modern lexicon corresponds to major milestones in our dawning awareness of the plight of the natural world, such as the publication of Rachel Carson’s seminal Silent Spring in 1962. Yet talking about the degradation of the environment rather than of nature also reflects a subtle cognitive shift towards increasingly seeing human beings as exceptional distinct entities surrounded by a natural world from which we derive benefits.

The clockwork universe

This western perspective of humans as separate, self-interested, and self-sufficient accelerated since the 1960s, but it actually reflects a longer historical trend. Since the 17th century, a rationalist worldview prompted by philosophers such as René Descartes increasingly saw the world from a mechanical perspective, comparing the workings of the universe to a great machine. Rather than any kind of divine spirit inhabiting the natural world, this perspective emphasised the split between mind and physical matter. Anything non-human fell into the latter category and was likened to clockwork machinery.

This segregation of humans from the natural world went hand in hand with seeing individual humans as sovereign and isolated from one another. Modern western culture has taught us to celebrate a distinct self, even to the extent of creating one’s own personal ‘brand’. Various governments have told us that there is no such thing as society or that ‘greed is good’. We have developed an economics framed around increasing utility, treating the natural world as a new type of capital providing quantifiable services to meet individual needs.

So, where does all this lead? Not surprisingly perhaps, seeing oneself as excessively isolated leads to loneliness. Today, we suffer from a mental health crisis where one in six adults in countries like the UK and USA are on antidepressants, and anxiety and self-harm are rife among our children. We are also facing daunting challenges from climate change, ocean acidification, biodiversity loss, air pollution, pandemics, and more. Perhaps that’s not surprising either: environmental psychology suggests that when we feel less connected to the natural world, we’re more likely to treat it like a consumable resource.

How we ‘self-isolated’ from nature

Perhaps we shouldn’t blame our modern culture completely. Homo sapiens actually evolved biologically to have a distinct sense of self because it helped our survival in prehistoric times, likely aiding us to gather food and navigate complex social interactions. Yet, in the modern world, without the checks and balances on selfishness that living in small closely-knit social groups provides, excessive individualism and atomisation have become maladaptive.

Just as how the urge to gather high energy (sugary and fatty) food was once adaptive but is problematic in the modern world, so too does our evolved sense of individuality now lead us astray. This is especially so when our media, governments, education systems, and economic institutions combine to push the pendulum ever further away from collective identity towards excessive selfishness. Instead of curbing our evolutionary biases, cultural and biological evolution are in a runaway waltz. We’ve developed a world that all too often brings out the worst in us: a veritable breeding ground for narcissism, xenophobia, and ecocide.

Yet all is not lost. While it may seem as though the modern western perspective has steamrolled all others, there are other – perhaps more sustainable – ways of seeing ourselves in relation to other people and the natural world. The Nayaka people in the Gir Valley of south India, for example, see nature as an ancestor, referring to natural spirits as ‘relatives’. This emphasis on connectedness with nature is found in many indigenous cultures around the world and has shaped more sustainable relationships with nature that have often endured for thousands of years.

This was something that scientists leading the world’s biggest assessment of biodiversity change discovered to their detriment. The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) previously framed nature using a utilitarian perspective, focusing on its potential to provide services to people. This was heavily rejected by many countries, especially in the global south, and the IPBES had to concede to a more plural framing of nature.

The science of connectedness

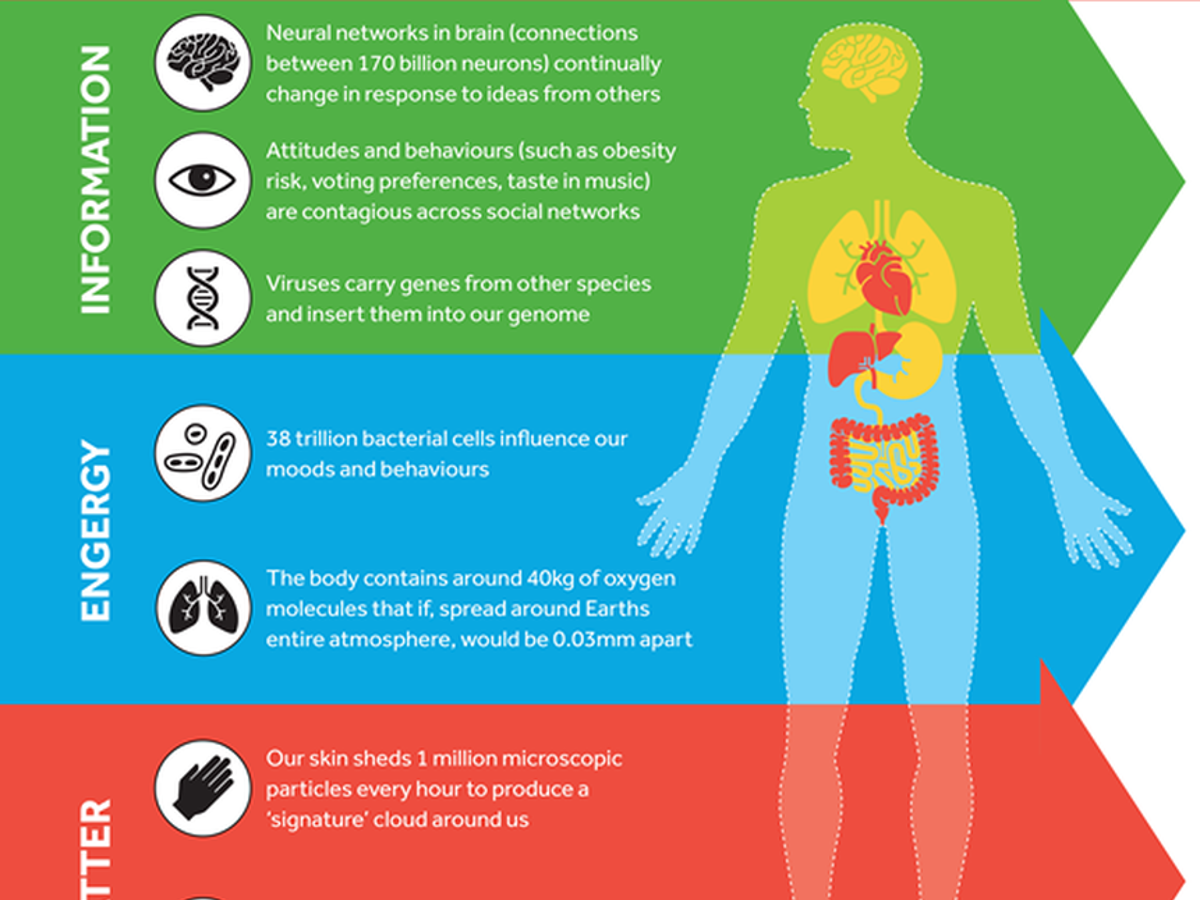

Although less mainstream, worldviews that emphasise our deep interconnectedness with nature are actually more strongly supported by recent science. There has been an explosion of research across disciplines such as biology, neuroscience and psychology, the findings of which challenge so critically the paradigm of individual human exceptionalism, that its days must surely be numbered.

For example, we like to think of our bodies as exclusively ‘human’, but right now each of them contains over 38 trillion bacterial cells. Bacteria live in our blood, brains, and on our skin in huge numbers (there are an estimated 440 species living in between your elbow joints and around 1,000 species in your mouth). What’s more, each of our human cells contains tiny ‘organelles’ that were once free living bacteria.

The body is an open system renewing itself daily with new materials (many of our cells are just a few days or weeks old) and maintaining a permeable boundary to mediate flows of energy, matter, and information. All this is directed by DNA code that is simply borrowed from our ancestors and which we will pass on to ancestors to come – DNA that is composed, in very large part, of genetic code that was once part of viruses.

Some may be tempted at this point to argue that our bodies are part of the ‘environment’, but our minds are separate (doubling down on the Cartesian split of mind and matter). Yet this, too, would be wrong. Evidence shows that our minds are embodied: our nervous system extends below our brain to wrap itself around our gut so that bacteria in our intestines affect our moods and behaviours, detracting from our supposed individual autonomy. Our body is also filled with viruses, fungi, and single celled organisms called protozoa that have hidden influences on us. For example, a protozoa called Toxoplasma gondii affects our risk-taking behaviour. Even the smells from other species nearby can affect us, fomenting anxiety or happiness, all below the conscious radar.

It’s hard to see a unique, distinct human individual in all this! What we see instead is that the idea of nature existing ‘out there’, rather than within, is not consistent with science; sovereign individuality is little more than an illusion. So, do we need to be teaching about the human relationship with nature in a different way?

Challenging the status quo

A quick quiz now: how many degrees taught in your local university prompt students to enquire deeply about the human relationship with nature? I’m guessing the answer in most cases is ‘not many’; philosophy perhaps, and maybe biology and geography, though only if the tutor is intrepid enough to dig below the mainstream view.

Next question: how many different sectors of the economy are fundamentally influenced by our human/nature relationship? Personally, I find it hard to name a single sector that isn’t affected by hidden assumptions about how humans should relate to the natural world – whether it’s the way we run our economy, design towns, spend on healthcare, or make legal judgements.

When we conceive of ourselves as isolated from nature, our institutions exacerbate the crises in sustainability and mental health that we suffer from today. But what would it take to transform our institutions? How can we break though the mantle of baked-in ways of thinking and acting? It’s hard to change worldviews when you’re older – identities and attitudes are literally hard-wired and can be tricky to budge. So I place great hope in younger generations who may come to see the world very differently to us.

Yet there we face a challenge too: research suggests that our sense of nature connectedness tends to drop at around the age of 11 and doesn't recover until early middle-age. While children, it seems, feel intuitively linked to the natural world, western society appears set to press this out of them as they grow older, creating atomised (and lonely) individuals daunted by taking on the world ‘out there’.

So I think we must ask: should our schools and universities be places which transform students to prepare them for the workplace, or should they instead prepare students to transform the workplace? Millions of students pass through schools and universities globally to enter the workplace each year. Will they simply adopt the status quo in terms of how those sectors function? What if, instead, we could create a fundamental pivot in the way we teach about human/nature relationships across all disciplines? Could we reverse the teen-year decline to restore a radically enhanced sense of nature connectedness?

Nature’s happy ending?

If we can re-orient the way we think about ourselves and the natural world – from being apart from it (and surrounded by it ‘out there’) to instead truly feeling a part of it – then evidence shows it will lead to better mental health outcomes and more pro-environmental behaviours. Who knows, it might just catalyse the tipping point in institutional change we so urgently need if we are to develop a more sustainable course for humans and the multiplicity of other species with which we are so deeply enmeshed. So, personally, I’m happy to see ‘the environment’ disappear as soon as possible.

Tom Oliver is Professor of Applied Ecology at the University of Reading, UK, and author of The Self Delusion: The Surprising Science of Our Connection to Each Other and the Natural World.

Image (used top): 'Origin of life’ by Odra Noel, courtesy of the Wellcome Collection and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0