When sport is entwined with religious and political allegiances, can it also bring communities together? By Owen Hargie, Ulster University, Ian Somerville, University of Leicester, and David Mitchell, Trinity College Dublin at Belfast, UK

When sport is entwined with religious and political allegiances, can it also bring communities together?

By Owen Hargie, Ulster University, Ian Somerville, University of Leicester, and David Mitchell, Trinity College Dublin at Belfast, UK

A deep religious, cultural, and political fault line runs through Northern Ireland, with Protestants and Catholics divided across it. They tend to live in different areas, study in segregated schools, and have friends and partners from the same religion. They celebrate divergent cultural heritages, embrace deviating narratives about the causes of the conflict, and vote for diametrically opposed political parties. For many young people, their first experience of interacting with those from the other religious community is in tertiary education or work.

The entrenched divisions emanating from these politico-religious differences led to overt physical conflict during a period known as the Troubles, in which more than 3,700 lives were lost. This created a legacy of hurt and a desire for justice, passed down through generations. It also served to deepen the ingrained attitudes of the two main rival blocs: Protestants, unionists and loyalists who are pro-British and wish to remain part of the UK, and Catholics, nationalists and republicans who are pro-Irish and wish to leave the UK and unite with the Republic of Ireland.

These political divisions are very evident within sport, with some sports being divided along sectarian lines. Here, as elsewhere, sport can be a symbol of religious, cultural and political allegiances, and an incubator for separation and prejudice. But can it also have the opposite effect?

Experience suggests it does. By bringing people from different backgrounds together in a shared enterprise, sport can build social cohesion across identity divides. It can be a way to foster cultures of peace and tolerance within communities and empower marginalised groups. And then there’s its symbolic power: the image of unified teams, colours, and emblems can evoke a powerful message of inclusivity and political change in the popular consciousness.

This power of sport both to unify and divide has given rise to a growing body of research on the relationship between sport, politics, and peacebuilding in Ireland, which has focused primarily on Northern Ireland’s three main spectator sports: Gaelic games, rugby and football.

The state of play

Gaelic games are unique to Ireland and include Gaelic football, hurling, and camogie – the latter both stick-and-ball team sports, with camogie played only by women. These are governed by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA), which since its founding in 1884 has maintained a close relationship with the Catholic church and an explicitly nationalist ethos. Its clubs were formed in line with Catholic parishes, its games are central in Catholic schools, and its main stadium is named after an early patron and Catholic archbishop, Thomas Croke. An example of the essential duality here was when Sean McCarthy, an early president of the association, affirmed that if you were not ‘Catholic and a member of the GAA, you could not be a good Irishman’.

The GAA has since established an outreach programme to build cross-community links and work with schools that wouldn’t normally engage in their sports. And in 2020, a GAA club was formed in East Belfast, a predominantly Protestant area, with a crest comprising symbols which are deliberately inclusive: the cranes of a Belfast shipyard, a sunrise, the Red Hand of Ulster, a shamrock, and a thistle.

Yet the symbiotic relationship between the Gaelic games and the Catholic church remains little changed in Northern Ireland, where membership of the GAA remains almost exclusively Catholic and bound by its constitution to ‘the strengthening of the National Identity in a 32 County Ireland’ – a reference to a pre-partition state. More controversial has been the naming of some grounds, trophies, and competitions in memory of republican terrorists. The recent unveiling of a memorial plaque to three former IRA men at a GAA club in County Tyrone for example, caused deep offence to members of the Protestant community who regard the IRA as a terrorist organisation. All this makes it difficult for those who identify as British to take part in Gaelic games.

Football, on the other hand, is played both by Catholics and Protestants, although many teams are segregated – usually because of geographical location. Northern Ireland’s international team, which has always included Catholic and Protestant players and staff, has mainly Protestant or unionist supporters, while many northern Catholics or nationalists traditionally follow the Republic of Ireland. During the Troubles, football and other sports provided an outlet for the expression of political sentiment, with sectarian chanting echoing from the stands.

While football today reflects the partition of Ireland, this was not always the case. Until the 1921 partition, the whole island was represented by a single team and, until 1953, two ‘Irelands’ played international matches, with players selected from across both jurisdictions. This led to FIFA’s decree that the two teams must instead reflect the separation of north and south.

Rugby, by contrast, is often vaunted for avoiding the sectarianism that has plagued the other two sports. Spectators from north and south, Catholic and Protestant, support a rugby team representing the entire island, while players also unite under the British and Irish Lions squad. A provincial rugby team represents the historic nine counties of Ulster, three of which are in the Republic of Ireland. This team can be embraced both by Protestants, who see ‘Ulster’ as a synonym for ‘Northern Ireland’, and by Catholics as Ulster is an ancient province of Ireland.

However, the rugby scene has not escaped the endemic sectarianism, with disputes over which flag and anthem should be flown and sung at matches in different jurisdictions. This was brought into focus in 2007 when the first international rugby game for 50 years was played in Northern Ireland. Prior to this, there was an apparent understanding within rugby that when an international game was played in the north or south, the anthem and flag of that jurisdiction would be used. At this Belfast game, however, the Dublin-based Irish Rugby Football Union did not allow the flag or anthem of the UK to be employed, treating the match as an ‘away’ fixture instead. Indeed, it is now the Union’s official policy that only the neutral anthem ‘Ireland’s Call’ is used at matches outside of the Republic of Ireland jurisdiction, but for ‘home’ games (which now exclude Northern Ireland) both the Irish anthem (‘The Soldier's Song’) and ‘Ireland’s Call’ are sung. While this decision may be acceptable to Catholic rugby fans, it has not been so well received by many from the Protestant community.

The issue of anthems is divisive across all three sports: the GAA also employs the ‘The Soldier’s Song’ at many of its games, while at Northern Ireland’s international football games, the UK anthem ‘God Save The Queen’ is played, creating problems for Catholic players and fans.

Seas of green

As these examples show, Northern Ireland’s three main sports clearly echo wider divisions. And yet the political changes brought about by the peace process have enabled moves towards greater inclusivity in sport. Sports-based reconciliation initiatives across all three sports have contributed to the improvement of hostility between divided communities, with the Irish Football Association (IFA), Ulster Rugby, and the GAA coming together to promote peace and reconciliation under the umbrella title ‘Sport Uniting Communities’.

But it is in football where the most significant change has occurred – a transformation that can be traced back to 1998, when the IFA appointed its first community relations officer. This was also the year of the Good Friday Agreement, which recognised for the first time the right of all citizens of Northern Ireland to identify themselves, and be accepted, as British or Irish, or both. In 2000, the IFA launched its much-lauded Football For All campaign, which included strategies to eliminate the sectarianism that had blighted games – including promoting a ‘sea of green’ to replace sectarian colours and symbols.

This campaign was highly successful. In 2006, Northern Ireland fans were awarded the prestigious European Football Supporters Award, which recognises supporters’ efforts to promote a friendly atmosphere at matches. And, in 2016, fans from Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland were collectively awarded the Grand Vermeil – the prestigious Medal of the City of Paris – for their ‘exemplary sportsmanship’ during Euro 2016. The two sets of fans were described as ‘a model for all the supporters of the world’ for the way they backed their teams and contributed to a positive atmosphere in host cities across France.

Of course, progress in the sporting domain has been helped by societal shifts and a gradual transition to a more peaceful society. Recent years have witnessed the growth of a new, cross-community Northern Irish identity. In fact, the largest portion of people no longer identify themselves as ‘Unionist’ or ‘Nationalist’ but rather as ‘neither’. This emerging Northern Irish identity is particularly associated with a post-conflict generation, for whom sectarian division and conflict has been less prevalent. It means that people can feel they are Northern Irish but can also identify with being Irish or British. While studies have shown that this new identity can be ambiguous and mean different things to different people, it also represents a growing sense of shared identity that offers sporting bodies exciting opportunities for inclusivity.

Change…and continuity

Our own research points to both continuity and gradual change in Northern Irish sport, which reflects the distinct quality of peace in the region. In one of our main studies, we found a widespread public belief in the peacebuilding capacity of sport. A significant majority agreed that sport is effective in breaking down barriers, and those who had actually participated in sports-based peace initiatives were significantly more likely to endorse their bridge-building benefits. Many people had positive experiences of meeting people from different backgrounds in a wide range of sporting settings. However, and perhaps paradoxically, a majority did not see anything wrong with different sports or teams being exclusively or mainly played or watched by Protestant or Catholic communities alone. Nor did they believe there would be significant change in the religious make-up of such sports.

Thus public faith in sport’s unifying capacity must be seen in the context of Northern Ireland’s complex and contradictory political condition. On the one hand, public attitude surveys show high levels of support for initiatives such as mixed-identity housing, workplaces, and schools. Yet on the other, numerous indicators – such as the dominance of unionist and nationalist political parties, disputes over national symbols, and the persistence of patterns of segregation – suggest a degree of contentment with division, and the resilience of traditional opposing identities.

This observation is echoed in the peacebuilding literature where it is argued that civil society relationship-building can mask genuine conflicts of interest that need to be resolved as part of a sustainable peace process. It remains to be seen whether sporting bodies are ready to make the necessary substantial and transformative changes that would lead to total inclusivity.

Dr Owen Hargie is Emeritus Professor of Communication at Ulster University, UK.

Professor Ian Somerville is Head of the School of Media, Communication and Sociology at the University of Leicester, UK.

Dr David Mitchell is Assistant Professor of Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation at Trinity College Dublin at Belfast, UK.

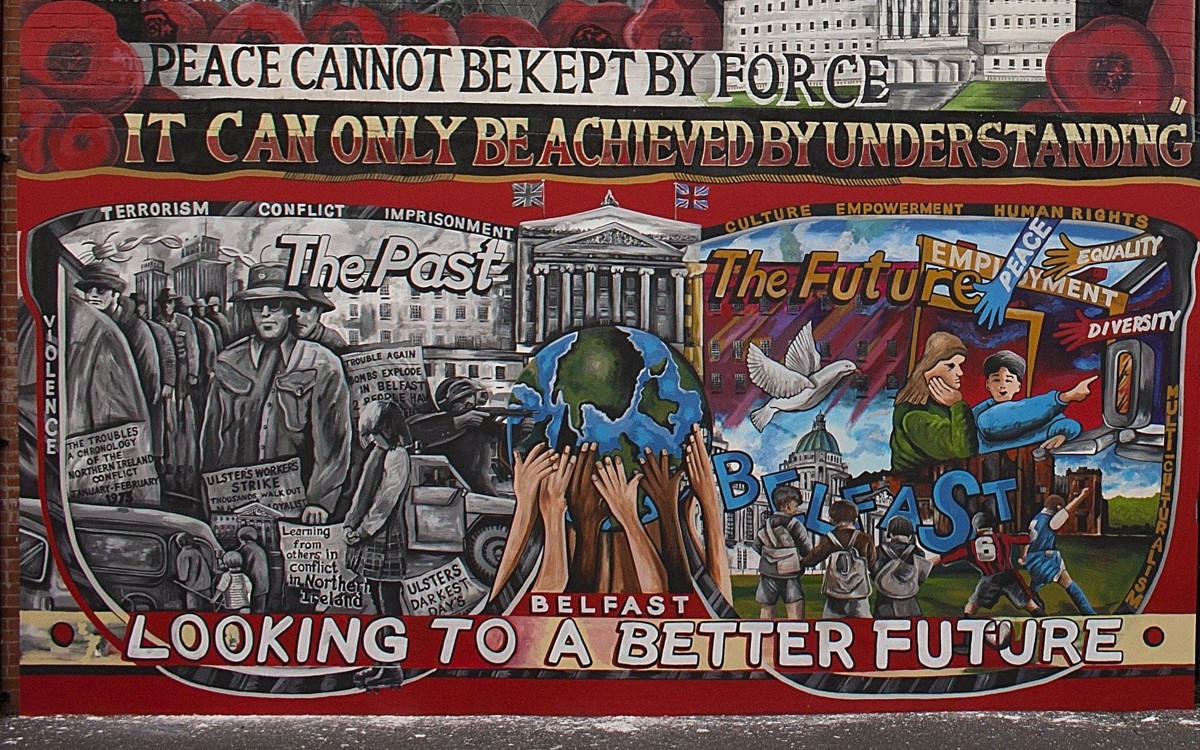

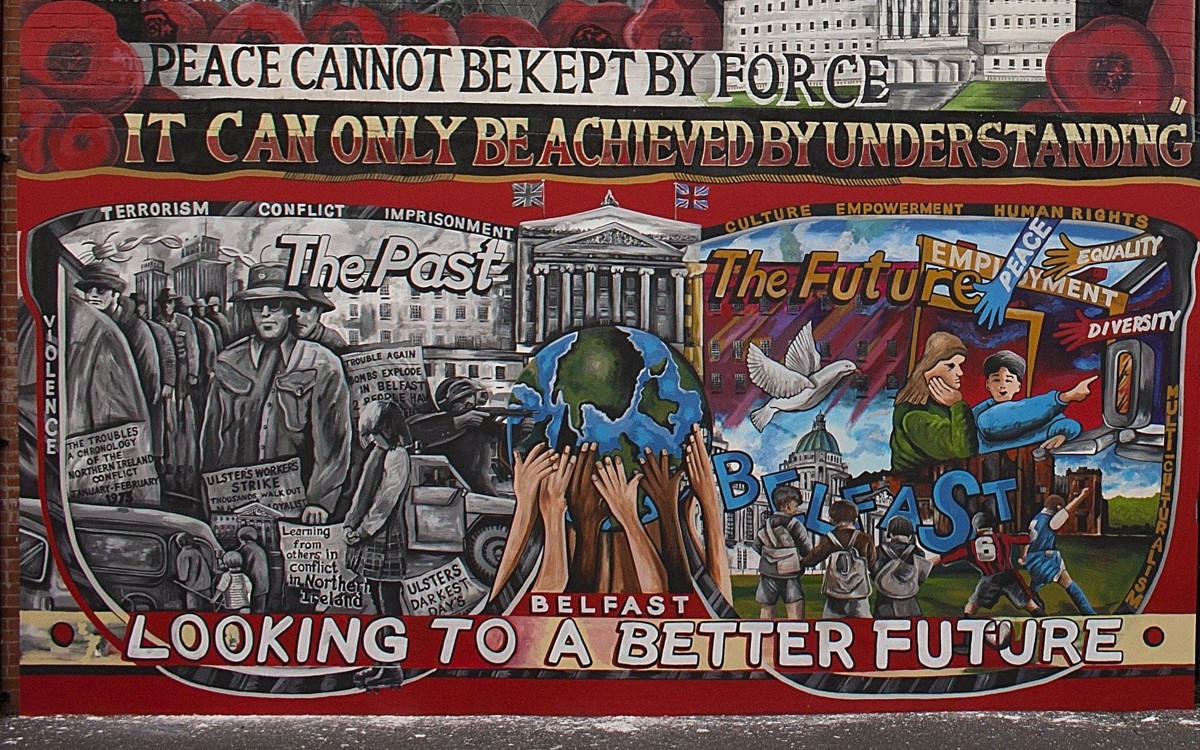

Images: Mural 'A better future' © Extramural Activity 2013. Camogie players by D. Ribeiro/Shutterstock. Northern Ireland fans at the Euros by PA Images/Alamy.