How two giants of the struggle against apartheid embraced the power of sport. By Marion Keim, University of the Western Cape, South Africa

How two giants of the struggle against apartheid embraced the power of sport.

By Marion Keim, University of the Western Cape, South Africa

When Archbishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu passed away in Cape Town in December 2021, his passing left a deep void in South African society. He was the voice of the voiceless, the nation’s moral conscience, a tireless fighter for peace and reconciliation, and a model of ethical leadership and moral justice. He was also one of South Africa’s most ardent sports fans.

I can say without fear of contradiction that there was no sport he did not love or believe had the power to enhance our humanity and interconnectedness. He particularly loved team sports and spent many hours watching, taking part in, and championing sport and its value to society as a whole and to young people in particular.

When I first met the Arch (as he was affectionately known) in 1994, he shared with me his reflections on sport as a tool for peace. ‘I often find myself thinking about joy,’ he said. ‘What is it? How does it happen? Is it complicated? Is it simple? Why do some seem to have it and others not? Have we been too weighed down by our past to recognise the joy that exists for us each day? If so, how do we recapture it? We have, I hope, spent many hours in serious discussion about how we might overcome past divisions and hate… But they are difficult and often painful discussions, with little opportunity for laughter and joy.’

Sport, on the other hand, seemed to represent to him that elusive joy. We both felt it offered a glimpse of another road to a future of equality and democracy for all South Africans – a road not filled with the hurt of those long discussions that carry us into the night, yet one that was equally important in its capacity to heal. ‘Is not the laughter of children playing together in a game of soccer, volleyball, rugby, or netball... something of beauty, something that is about joy?’ he wrote. ‘Is not teamwork something beautiful to behold in our new South Africa when the team is made up of different colours?’

The power to unite

The Arch was not alone in his fervent belief in the peacebuilding power of sport. Indeed, it was his friend Nelson Mandela who declared that sport had the power to change the world. ‘It has the power to unite people in a way that little else does,’ he said. ‘It speaks to youth in a language they understand. Sport can create hope where once there was only despair.’

When Mandela became South Africa’s first democratically elected president in 1994, he was acutely aware of the political impact of sport in the country, and actively used it as a tool to transform and unify a divided society and to redefine South Africa’s international image. It was, he would later say, more powerful than governments in breaking down racial barriers.

In 1997, Mandela received the International Fair Play Award – usually given to an outstanding athlete. By honouring Mandela for embodying fair play in his public life rather than on the sports field, it was a reminder that the principles of fair play are a foundation not just of sport but of all social interaction.

Both Mandela and the Arch were supporters of Olympism and the Olympic values of friendship, respect, and excellence. The philosophy of Olympism places sport overtly at the service of the ‘harmonious development of humankind’, with the aim of promoting a peaceful society concerned with the preservation of human dignity. The Arch was not only an avid spectator of the Games but a flag bearer too. And in 2004, Mandela memorably carried the Olympic flame past his former prison cell on Robben Island as part of its ceremonial journey across the globe.

The idea that sporting competition between nations can play a role in promoting peace has been part of the Olympics since its origins. The ‘Olympic Truce’ dates back to the ninth century BC, when a treaty between the kings of three endlessly embattled states saw fighting cease for long enough to allow athletes and spectators from all regions to take part. Today, the Olympic Truce remains a symbolic concept, encouraging the search for peaceful and diplomatic solutions to conflicts around the world and emphasising the power of sport to promote peace and dialogue.

Levelling the playing field

In 2002, I approached the Arch to write the foreword to my book on sport as a tool for social integration in post-apartheid South Africa, which he was happy to do. It was the first scientific research looking at the role of sport as a tool for peace and nation-building in South Africa and argues that while sport undoubtably has a meaningful role to play in the social transformation of South African society, its success depends to a large extent on the way in which sport is organised and presented.

Sport in itself doesn’t necessarily help to break down the walls that divide us. On its own, it cannot reverse poverty, prevent crime, solve unemployment, or respect human rights. In fact, poorly organised sporting activities can actually deepen divisions and reproduce the inequalities that we want so desperately to overcome.

It is often proposed, for example, that linguistic and cultural barriers are more easily overcome in sport, thanks to its reliance on non-verbal communication and its simple symbolism. Yet in countries like South Africa, these linguistic barriers may not always be so easily disregarded. This points to the need for multilingual coaches, trainers, and teachers who can navigate the team-building process in an inclusive way and promote respect.

Similarly, sport is sometimes vaunted for its power to transcend socioeconomic divisions, particularly among children and young people. Yet in South Africa, sport can also accentuate these divides. Access and opportunities to take part in sport remains unequal and often restricted for disadvantaged communities – the result partly of the legacies of apartheid and the accompanying lack of sports facilities in African townships.

These complex challenges and opportunities mean that leaders in sport cannot shy away from public dialogue about sport and social responsibility, nor from meaningful investment in sport programmes and facilities in our schools and communities. Meanwhile, the coordination of group sports opportunities – whether within or between schools, in neighbourhood clubs, or professional leagues – must be sensitive to language, background, religion, and cultural heritage. They must pay careful attention not only to the choice, accessibility, and location of sports facilities, but to the transport that gets people there and the infrastructure that supports them. These factors are all part of creating a level playing field for sport to build on.

Legacies and hope

While we must be cautious of raising expectations of sport that cannot be met, we also shouldn’t overlook its power to take us forward as a nation and as a global society. It’s an ideal captured in the Olympic vision: to bring about a peaceful and better world through sport practiced without discrimination at the service of the harmonious development of humankind.

Opportunities exist for sport practitioners and interested readers to become involved in sport for development and peace initiatives. Coaching development and Olympic Values Education training by the South African-based Foundation for Sport, Development and Peace in collaboration with the IOC, for example, or the annual International Sport and Peace Conference in Cape Town are just some of the opportunities to work together to achieve this true meaning of Olympism for all of us.

Nelson Mandela and the Arch embraced and epitomised the Olympic spirit of mutual understanding, friendship, solidarity, and fair play, and we can honour their legacy by embracing these values on the sports field and in our families, communities, and societies. If we can learn to play together with respect and with laughter, then perhaps we can learn to be all on the same team and, in the process, contribute to building a more just nation for all.

Dr Marion Keim is Professor and Director of the Interdisciplinary Centre for Sports Science and Development at the University of the Western Cape, South Africa, a member of the IOC Olympic Education Commission, and the Chairperson of the Foundation for Sport, Development and Peace. Her book Nation Building at Play, with a foreword by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, is published by Meyer and Meyer Sport.

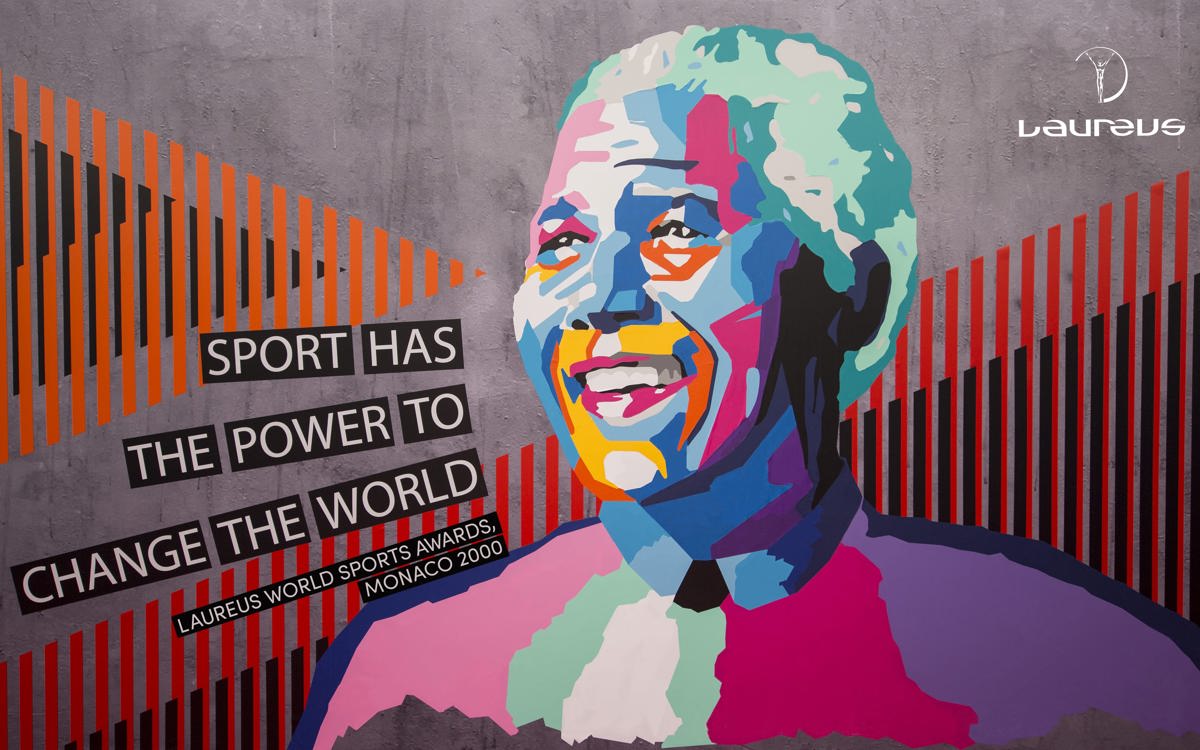

Images (from top): Archbishop Desmond Tutu by Reuters/Alamy Stock Photo. Nelson Mandela artwork © Laureus World Sports Awards Limited. Image of Caster Semenya by Celso Pupo/Shutterstock.

All content published by The ACU Review is copyright of the Association of Commonwealth Universities or its licensors and may not be reproduced without written permission from the Association of Commonwealth Universities. Please contact review@acu.ac.uk with enquiries.

How can we break the vicious cycle of poverty and mental health for young people living in adversity in South Africa and beyond? Read The Vicious Cycle by the University of Cape Town's Emily Garman in The ACU Review's public mental health issue.