Why the world of sport needs to engage with the politics of peace. By Simon Darnell, University of Toronto, Canada

Sport’s peacebuilding power stems not from a mythical ability to transcend conflict, but from engagement with the tricky politics of peace.

By Simon Darnell, University of Toronto, Canada

The relationship between sport and the pursuit of peace is at once an inspiring and a cautionary tale. In 1914, sport contributed to a fleeting ‘Christmas Truce’ during World War One, when British and German soldiers crossed the trenches of the Western Front for an impromptu game of football. In 1995, the South African national rugby team – inspired by new President Nelson Mandela – hosted and won the Rugby World Cup, playing in the tournament for the first time since the end of apartheid and demonstrating a role for sport in national reconciliation and healing. And in 2013, the United Nations named April 6 as the annual International Day of Sport for Development and Peace, commemorating the first modern Olympic Games in Athens in 1896, and calling on sport to contribute to peace and reconciliation on a global scale.

And yet, sport also has a rather dubious record in relation to peace. In 1969, the 100 Hour War between El Salvador and Honduras, also known as the Football War, started after riots during a World Cup qualifying match between the two countries ignited existing tensions. A riot between supporters of Dinamo Zagreb and Red Star Belgrade in 1990 took place on the eve of the violent break-up of Yugoslavia, and helped to foment the war that was to come. And more recently, athletes who’ve used sport as a platform to speak out against racism and police violence have found themselves vilified by fans, reporters, and politicians, suggesting that at some level, sport has failed to provide a platform that unites people around peace and understanding. These examples hearken back to George Orwell’s infamous quotation that serious sport is ‘war minus the shooting’.

So, what does this rather checkered past tell us about sport and its potential to contribute to peace, conflict resolution, or universal understanding today?

Can we reasonably expect sport to make the world a more peaceful place?

First there is the question of what sport offers in and to a globalised and interconnected world. It’s worth reflecting on the fact that sport is undoubtedly a globally recognised cultural form. The FIFA World Cup final, for example, remains the world’s most-watched broadcast event and, around the world, people engage in sports and physical cultural activities in ways that transcend language, geography, or social class. This suggests that there is at least an opportunity to unite people around the common interest that global sport provides.

However, sport is not a replacement for the often-messy politicking, and the deeply human activities, that are necessary to achieve peace. The case of Mandela and the 1995 rugby World Cup is instructive here. Whereas the popular narrative of the event, constructed through Hollywood films like Invictus, often give credit to the unifying power of sport for healing South Africa’s divisive racial history, a more accurate reading is that peace through sport was possible because, at every turn, Mandela resisted the calls and opportunities to descend into a race-based civil war, and instead chose to pursue a politics of reconciliation and forgiveness.

Without doubt, sport and the ‘95 World Cup were well positioned to support his approach, and Mandela leveraged rugby brilliantly. But the real work was the struggle to let go of the pain and violence of apartheid in the name of healing. That Mandela led this process with grace and conviction cannot, and should not, be reduced to or explained away as simply exemplary of the ‘power of sport.’ This importance of humanising the relationship between peace and sport remains today, even though Mandela himself stated that ‘Sport has the power to change the world. It has the power to inspire. It has the power to unite people in a way that little else does.’

A third implication, then, is that sport’s potential contributions to peace and reconciliation do not emerge from, or rest in, its apolitical position or mythical transcendence of violence and conflict. Indeed, one only needs to think again of Orwell, or of the current popularity of mixed martial arts, or the fundamental violence of sports like American football, to reject the thesis that sport somehow exists beyond the realm of violence.

Instead, it is only when the world of sport, and the leaders of sport, are willing and able to engage politically that sport’s peace potential might be realised.

Stepping up from the political sidelines

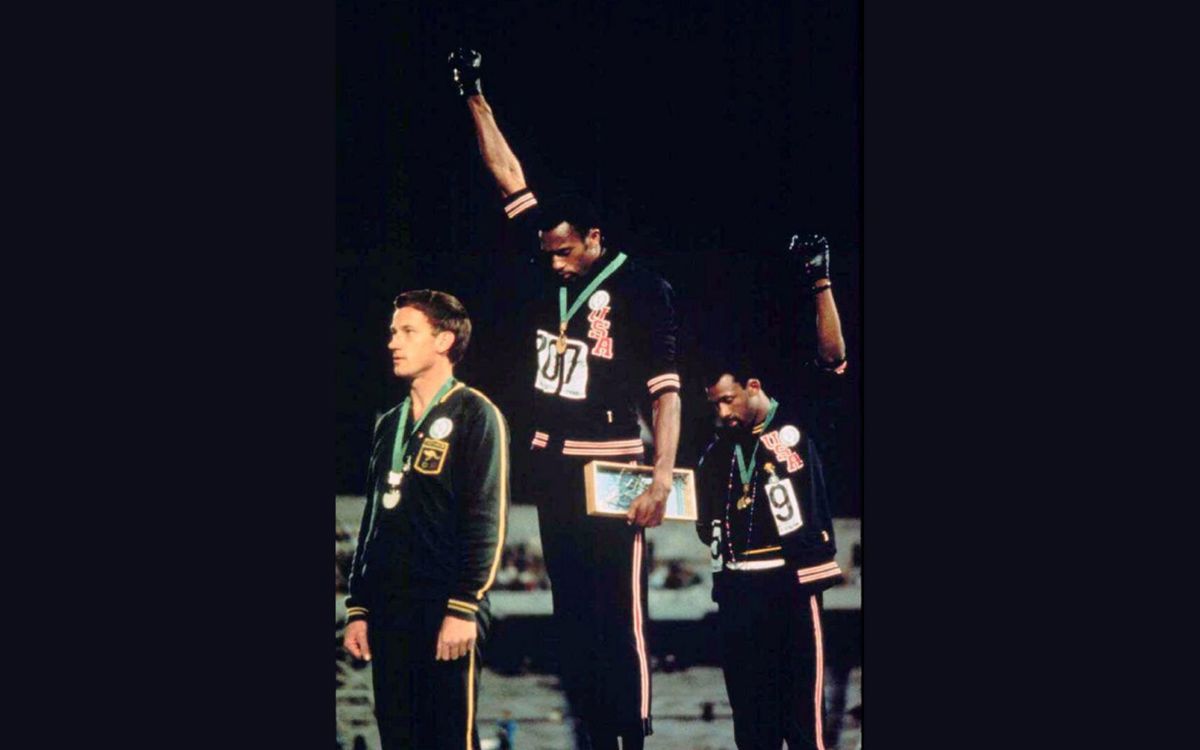

This is, admittedly, an unpopular perspective in that it stands at odds with the unyielding efforts of major sporting stakeholders, most notably the International Olympic Committee (IOC), to steer sport clear of politics. A most recent example of this is the IOC’s Rule 50, designed to prevent political demonstration by Olympic athletes during the Games – a policy with clear historical reference to John Carlos and Tommie Smith’s gloved-fist salute on the Olympic podium at the 1968 games in Mexico City in support of the Olympic Project for Human Rights.

Instead of contributing to peace, policies like Rule 50 are a fool’s errand, for several reasons. The first is that attempting to implement rules to prevent social and political activism in sport completely misreads the fact that activists – whether athletes or not – are largely unconcerned with following conventions. Indeed, that is what makes them activists! Second is that audiences, both sports fans and non-sports fans alike, remain deeply interested in what athletes have to say on political matters, even if they disagree.

So, even though athletes such as American footballer Colin Kaepernick – who, in 2016, was the first athlete to take the knee – have faced significant backlash for protesting against racism, it is also the case that his efforts, and those of others around the world, have served to solidify and advance social movements such as Black Lives Matter.

While the peaceful outcomes of these efforts might not be immediately visible today, recognising that the long arc of morality bends towards justice means that sport and athletes are laying the groundwork now for peace and social change that is to come. This can only happen, however, when sporting organisations are willing and able to suspend their financial and branding interests when presented with the challenge of organising sport in the struggle for peace. The recent expulsion of Russian sport from most international sporting competition in response to the invasion of Ukraine is encouraging; the tacit acceptance by the global sporting community of China’s ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya minority during the 2022 Beijing Olympics is less so.

What is called for then, and sorely needed in these times of military aggression, climate emergency, and the ongoing fallout of a global pandemic, are organisations, policies, and leaders within sport that support a strong, ethical, and direct engagement with the political struggle for peace and justice. Attempts by sport leaders to bury their heads in the sand of neutrality will only allow conflict to continue, while exposing the complicity of sport with injustice and inequality, and making hypocrites of those who enjoy expounding on sport’s peaceful foundations.

Worse, a failure on the part of sport leaders to engage with the politics of peace will render moot the powerful potential that global sport and celebrity athletes actually hold to make a positive contribution. Given the crises that the Earth is facing, the time is now for sports to get off the political sideline and get into the game of pursuing peace and justice.

Dr Simon C. Darnell is Associate Professor for Sport for Development and Peace and Director of the Centre for Sport Policy Studies at the University of Toronto, Canada.

Images (from top): Photograph of Tommie Smith and John Carlos by Abaca Press/Alamy. Athletes taking the knee by SPP Sport Press Photo/Alamy.

All content published by The ACU Review is copyright of the Association of Commonwealth Universities and all rights are reserved. You cannot reproduce any material published here without written authorisation from the Association of Commonwealth Universities. Please contact review@acu.ac.uk with enquiries.