The first of two articles on appearance-related concerns explores the pressures faced by young women in India, where sales of skin-lightening creams reflect a quest for impossible ideals of beauty. By Megha Dhillon, Lady Shri Ram College, India

Soaring sales of skin-lightening creams are just one sign that India’s young women are feeling the pressure to meet impossible ideals of beauty.

By Megha Dhillon, Lady Shri Ram College, University of Delhi, India

India, a country home to over 1.3 billion people, is characterised by extraordinary diversity in religion, customs, traditions and language. But its ideals of female beauty are far more uniform. Light skin tones and thin bodies are increasingly accepted as essential markers of beauty, leading many young women to reach for skin-lightening creams or develop deep anxieties about their appearance. What makes this even more worrying is that India is a nation of young people – more than half of its population is under the age of 25. As a professor and researcher at a women’s university college in India, I have seen at close hand the potent factors which perpetuate these ideals and leave so many young women struggling to meet the impossible demands of perfection.

Women under pressure

Mental health is a deeply gendered construct. In other words, there are gender differences in the nature of mental health problems experienced by men and women, their health-seeking behaviours, and how others respond to their concerns. In India, more women suffer from depression and anxiety disorders than men, and suicide is the leading cause of death among Indian women aged between 15 and 29. Although biological and sociological factors intersect to produce mental illness, the high rates of depression and anxiety among women reflect some of the social pressures and ordeals they confront, including marital pressures, domestic violence, and dowry-related harassment.

Many of these women will be unable to access the help they need. As elsewhere, mental health is a marginalised issue in India. The budget for mental health is less than 1% of India’s total healthcare budget, with fewer than two mental health professionals for every 100,000 people. This is despite the fact that a National Mental Health Survey commissioned by the government found that 150 million Indians were suffering from a mental health disorder.

A growing issue among young Indian women is anxiety around body image – negative feelings about their appearance and body shape that can take a significant toll on their wellbeing. Weight tends to be an important dimension: while earlier ideals of Indian beauty presumed a well-fed figure with rounded curves, this is no longer the case. And though food continues to be a symbol of hospitality and prosperity in Indian households, many urban women and girls now consider slimness to be a critical part of attractiveness.

In India’s urban centres, terms such as ‘size zero’ and ‘skinny’ have found their way into popular chatter, diet foods have become easily available, and gyms and fitness centres proliferate. Just as in other parts of the world, the Indian media play a critical role in the dissemination of appearance ideals. Actresses who fail to meet the media’s acceptable standards for weight, struggle to gain its approval and are expected to explain or defend their body shape during interviews and press conferences.

‘Fair and lovely’

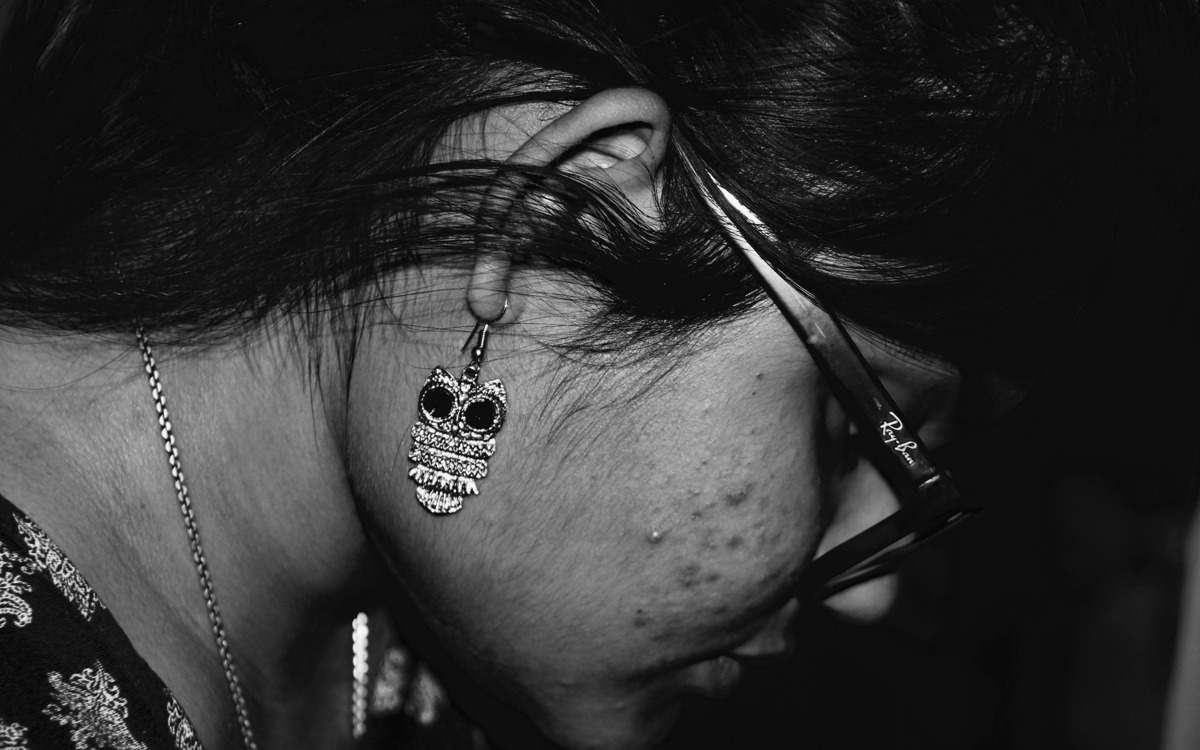

Skin colour is also considered to be a critical marker of beauty. Fairer skin is deemed desirable, whereas a dusky complexion, acne, circles under the eyes, body hair, and scars are causes of shame and embarrassment. Songs in Indian movies often make references to the fair and glowing skin of the heroine, explicitly linking lighter skin tones and blemish-free skin with beauty. The advertising industry, too, is unrelenting in its attempts to sell skin-lightening or fairness creams, such as the popular ‘Fair and Lovely’ range, conveniently neglecting Indian women’s genetic realities. The scale of the problem is reflected in the booming success of the fairness cream industry in India, which stands at about 450 million US$ and is growing by 17% every year.

Fairness creams are often endorsed by leading actresses of Indian cinema. A typical advertisement for such products will show a dark-skinned woman, often lacking in confidence and success, whose ‘transformation’ into a lighter skinned woman brings with it all the success, confidence, and romance she previously lacked.

Many trace this obsession with fairer skin to European colonialism, which perpetuated and reinforced a perceived connection between lighter skin and higher social standing. Some link this to the idea that the ruling rich stayed indoors, while the poor worked outside in the sun. Colonial notions around the superiority of fair skin colour in India may also have found echoes in the caste system, in which higher castes were perceived to be ‘fairer’ and superior.

The 'perfect' woman

Just as potent as the media and advertising are influences found within young women’s closest circles. Young women speak of their parents and peers as important figures of influence who, in their own unique ways, may reinforce the apparent necessity of meeting appearance ideals. These messages may be shared through appearance-focused conversations, comparisons with siblings or friends, and appeals to diet or exercise.

Marriage, too, may create another pressure: many marriages in India are still arranged through advertisements online or in newspapers, in which families seeking brides often state a preference for women who are fair and slim.

Many young women internalise these messages, accepting and absorbing these ideas so that they become part of their character and beliefs. They come to connect the achievement of these physical standards with their own self-worth. They may feel they are missing out on important things by failing to meet appearance ideals, such as getting the job they want or dating the partners they desire. And while the standards of beauty are invariably impossible to achieve, many women experience a sense of failure when they are unable to do so.

Learning self-compassion

But how can appearance ideals and the pressures they create be tackled? I believe what’s required is a complete overhaul in the way women’s bodies are spoken of and understood, both by men and women. A shift away from conversations that emphasise how bodies look to those that emphasise what bodies can do would benefit all genders. While healthy eating and exercise are usually spoken of in terms of weight loss, it is far more important to promote them as lifestyle practices central to wellbeing, rather than as tools to achieve a ‘better’ body.

An important way to change the discourse is to promote greater levels of media literacy among Indian teens, equipping them with the tools they need to take a more critical view of the messages they receive through the media – particularly social media. Women who grapple with self-esteem issues can benefit tremendously from learning to question and challenge practices that objectify women and instead come to see themselves more holistically. Asking how they feel about themselves once all the outside voices are hushed, surrounding themselves with positive people, and using the time and energy that they spend worrying about their appearance to work on causes larger than themselves may also be beneficial in combating a low sense of self-worth.

Finally, in the face of unrelenting messages that demand perfection, the practice of self-compassion can serve as an important protective factor for women. According to psychologist Dr Kristin Neff, self-compassionate people remain gentle, kind and understanding towards themselves when they fail or feel inadequate, rather than ignoring the pain or attacking themselves. Self-compassion is about accepting reality with warmth and kindness, rather than resentment.

In the context of body image, this means accepting one’s appearance just the way it is. It involves creating space in one’s mind for different, broader definitions of beauty, rather than just those promoted by the media, and understanding that ‘not being perfect’ is a universal human condition. There is absolutely no one in the world that is perfect. The more we open our hearts to this idea, the better and stronger we can feel.

Dr Megha Dhillon is Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of Delhi’s Lady Shri Ram College, India.

Dr Dhillon works collaboratively with the Centre for Appearance Research at the University of the West of England, whose work is also featured in this issue. Read more about it in ‘Pretty unfair’.

Images by Chehak Gidwani, a psychology student at Lady Shri Ram College.