Conflict, crisis, upheaval and loss can leave entire communities suffering from collective trauma. By Daya Somasundaram, University of Jaffna, Sri Lanka

All over the world, conflict, crisis, upheaval and loss can leave entire communities suffering from collective trauma.

By Daya Somasundaram, University of Jaffna, Sri Lanka

Our world is no stranger to disaster. Across the globe, millions of people experience catastrophic events every year: events that strike suddenly, often without warning, and bring death and destruction in their wake. We know that the survivors of these disasters need relief in the most tangible sense – food, shelter, medicine – if they are to recover and rebuild their lives. What is less well recognised is the importance of mental health support for those whose lives and communities have been torn apart.

Beyond survival

Disasters – both man-made and in nature – are so commonplace that many do not make the global headlines. Some we call natural disasters – earthquakes, floods, tsunamis, landslides, drought. These kill around 90,000 people and affect close to 160 million worldwide every year – a figure that looks set only to rise as extreme weather events become more frequent and intense. Such disasters disproportionately affect those who are already vulnerable – socioeconomically deprived, minority and marginalised groups, who tend to live and work in poorer, exposed conditions and have limited access to resources and support systems.

Man-made disasters, such as violent conflict and civil war, are catastrophic in a more chronic, drawn-out way. In modern warfare or terror attacks, the goal is often absorption and assimilation into a dominant culture or ideology. The minority is expected to forgo its own culture and identity and merge with, or become subservient to, another. When communities try to resist, ethnic or civil conflict erupts bringing bloodshed and terror to civilians and combatants alike, and forcing millions from their homes.

Death, destruction, deprivation, and displacement – we recognise these as the immediate consequences of traumatic events. But for many survivors, the physical injuries and upheaval are accompanied by mental health problems, both short and long-term, that can hamper recovery and disrupt work, family, community, and normal functioning.

Broken communities

When I began my career, the basic psychiatric training I had undergone did not prepare me to address the mental health consequences of these kinds of events. Trauma – the blow dealt to the psyche by an extremely distressing event – was not even in the syllabus. Coming to the UK as a Commonwealth Scholar gave me the opportunity to learn about the then emerging field of trauma studies in the late 1980s and to build networks with people from around the globe working in similar contexts. Since that time, I have had the unique experience of treating many people in northern Sri Lanka and Cambodia whose lives have been shattered by war and the catastrophic tsunami of 2004, as well as refugees from hundreds of conflict-affected communities at the Survivors of Torture and Trauma Assistance and Rehabilitation Service in Australia.

My research has focused particularly on the concept of ‘collective trauma’, where a shared traumatic experience inflicts a deep psychological wound on an entire community, severing the ties between people and groups, and damaging social cohesion.

Collective events and their consequences may have more significance in collectivistic – as opposed to individualistic – societies, in which family and community are a profound part of an individual’s identity and consciousness, and where the boundaries between the individual self and the outside become blurred. In such communities, traumatic events are experienced collectively and the impact also manifests at that level.

In communities affected by civil conflict, the looming, pervasive threat may cause a state of generalised insecurity and a rupturing of the social fabric. Often, a community’s implicit faith in the world order and social justice unravels, as those responsible for war crimes and human rights are not brought to book and are often rewarded. Here, the victims must bear it in silence – both collectively and individually.

The ties that bind

Collective trauma was first described by sociologist Kai Erikson following the Buffalo Creek disaster in 1972, when a close community in West Virginia, USA, was torn apart by a devastating flood. Erikson described collective trauma as a ‘loss of communality’: ‘When forced to give up these long-standing ties with familiar places and people,’ he wrote, ‘the survivors experienced demoralisation, disorientation, and loss of connection. Stripped of the support they had received from their community, they became apathetic and seemed to have forgotten how to care for one another.’

The phenomenon first became very obvious to me when working in post-war Cambodia. During the brutal Khmer Rouge regime of the late 1970s, all social structures – family, educational, and religious institutions – had been razed to ‘ground zero’ so as to rebuild society anew. A whole generation missed out on basic education. Mistrust and suspicion arose among family members as children were made to report on their parents. The essential unity, trust, and security within the family system – the fundamental unit of society – was broken.

These broken ties are a hallmark of collective trauma. The social fabric is torn asunder. People are uprooted from all that’s familiar to them. Indispensable members of the community – often leaders or breadwinners – are killed, disappear, or become separated. The very way that families and communities function is altered. Basic trust and hope is lost; the glue that held relationships and networks together is destroyed.

But this loss of commonality can also help us see how people might be helped to recover. As I treated individuals, it soon became obvious that there were deeper, more fundamental problems at family and collective levels that underpinned their mental health. It was clear to me that if individuals were to heal, then social and community trust, relationships, and structures had first to be rebuilt.

How to heal

How, then, can communities and individuals recover? My work suggests that if the balance, equilibrium and healthy functioning of the family and community can be restored, individuals, too, recover within this nurturing environment. Family and social support, networks, relationships, and a sense of community appear to be vital protective factors for individuals and their families, and central to their recovery. It is therefore crucial for communities to rebuild trust, social capital, and a collective sense of cohesion.

During my work with people suffering from depression or trauma in the wake of the 2004 tsunami, I found that less than 10% of survivors required professional help. What they needed instead were community-based interventions – befriending, sharing and listening activities, and support groups. Cultural rituals, practices and remembrance events seemed to aid the grieving process and helped individuals and communities to recover and find meaning in their suffering.

Finding ways to express traumatic experiences may also help people to heal. Many people feel relief after verbally or otherwise expressing what they’ve been through, which they may otherwise replay within their minds. ‘Bottling-up’ distressing thoughts or feelings appears to demand a psychological and physiological effort that, over time, can place a strain on the body and lead to physical health problems.

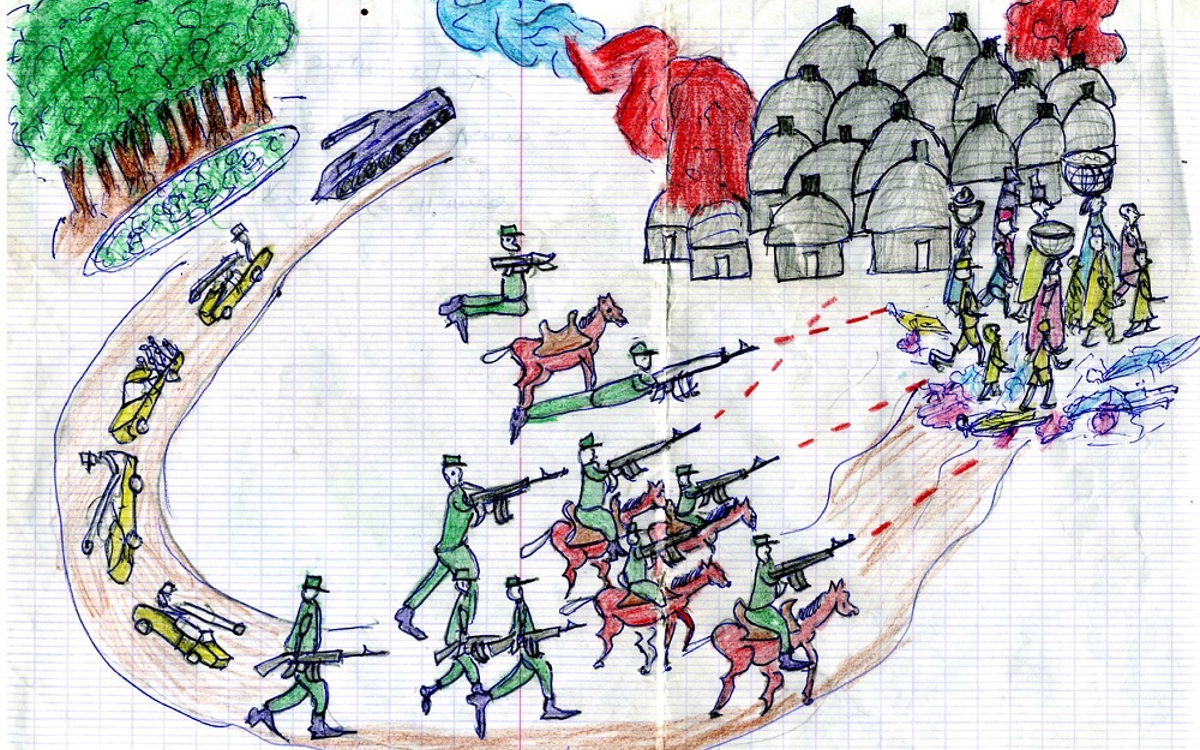

While cognitive behavioural therapy is one of the main approaches to treating trauma in the western world, cross-cultural trauma experts argue that such methods are often not appropriate elsewhere. Indeed, people from non-western countries may find modern psychotherapy strange and unacceptable. The answer, then, may be finding a culturally-appropriate way to enable thoughts and experiences to be expressed. This could include confiding in respected elders, traditional healers or priests, or self-expression through creative arts such as storytelling, drama, or drawing.

Another important approach is to promote a sense of calm through breathing, relaxation, and mindfulness techniques. This may sound simple, but can be therapeutic in countering the high levels of arousal, anxiety, fear, and avoidance that follow a traumatic experience. Again, this stress takes its toll on the body and, if left unchecked, can lead to a host of physical conditions.

While relaxation methods were only introduced into western medicine in the 1930s, physiologically similar methods have existed for centuries throughout Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. Pranayamam – the practice of breath control in yoga, and Anapanasati – a Buddhist form of mindful breathing – both produce conscious, deep, and regular abdominal breathing. Yogic poses such as Savasana bring about deep muscular relaxation, as can the traditional oil massage used in Ayurvedic and Shidda medicine. Mindfulness, the practice of focusing of one's awareness on the present, has gained incredible popularity in the past decade but has its roots in the early teachings of Buddha. Meanwhile other meditative practices – such as the repetition of a mantra or divine name – exist in many spiritual contexts, including the Hindu japa, Buddhist pirit or chanting, the Catholic Rosary or prayer beads, and Eastern Orthodox hesychasm.

A community-based revival of traditional relaxation methods may offer a calming force to counter the chaos and violence of chronic conflict. One approach is to teach traditional practices to large groups in the community, temples, churches, and as part of the school curricula. As well encouraging more people to benefit from these methods, bringing people together to learn and practice as a group can itself be therapeutic and socially healing.

As we look to the future, it seems likely that traumatic events will continue to cast a long shadow over individuals, communities, and entire generations. While countries, villages, homes and schools may be reconstructed, rebuilding the shattered lives and minds of those affected will take much longer. To help this happen, it is vital that we consider the type of psychosocial help required, as well as the cultural context in which it’s delivered.

When methods are culturally familiar, they tap into one’s childhood, community and religious roots and release a rich source of associations that can help the healing process. Although these techniques are not formal psychotherapy, they may accomplish the same, using cultural and spiritual processes that are resonant and restorative to a troubled mind.

Dr Daya Somasundaram is former Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Jaffna, Sri Lanka, and Clinical Associate Professor at the University of Adelaide, Australia. In 1988, he was awarded a Commonwealth Scholarship to study at the University of Leeds, UK.

Images (from top): Child's drawing of a tsunami , courtesy of Alan Liotard and licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0; Child's painting of a tsunami courtesy of UNESCO / G Boccardi.

The Darfur drawings are published courtesy of Waging Peace, whose researchers have collected over 500 drawings by children depicting the destruction of their villages during the genocide in Darfur and of their lives in refugee camps. Visit www.wagingpeace.info to learn more.