Plurality is more than tolerance or liberalism; it is an active recognition of the need for diversity.

By Shiv Visvanathan, OP Jindal Global University, India

The idea of cognitive justice appeared in a blurred way during my childhood. As children, we lived in the steel town of Jamshedpur. Every evening, we watched a ritual that fascinated us: late in the evening, the Tata steel plant would pour out its slag in a molten display. An hour later, the Dalma Hills were engulfed by flames as tribal groups cleared the land in a practice known as shifting cultivation or Jhum. My father, an eminent metallurgist, would watch both displays with fascination and an almost mystical expectation. He said: ‘As long as both exist, a balance exists; justice exists’. As children, we rarely understood him, but this article owes a lot to his insights.

Years later, as an anthropologist working in Gujarat, a group of tribal leaders and activists came to me saying they knew I worked in science and needed my help. They sat down and one of them said: ‘Can you arrange a seminar between our ojhas, our wiseman, our healers and western psychologists and psychiatrists?’ He explained that they did not want the usual World Bank concessions to participation or a subaltern sense of voice. ‘We want our theories to talk to their theories. Our democracy needs a citizenship of knowledge; a dialogue of knowledges.’

The leader asked me if I could coin a word for this process, a concept which unfolded what they wanted to say. I coined the idea of cognitive justice: the right of different knowledges to coexist so long as they sustain the life, livelihoods, and life chances of a people.

Museums or mausoleums?

The idea of cognitive justice established a framework of connections. It emphasised that knowledge cannot be reduced to science and that our community needs a dialogue of knowledges, not just an interdisciplinary encounter between the sciences. It sensed that science had become a hegemonic form of knowledge which was ‘museumising’ entire communities. Science, in its innovative obsessiveness, was refusing to recognise that obsolescence was a form of violence.

In this context, one recollects one of the memorable arguments during the debates on science and nationalism in India. The geologist and art historian, Ananda Coomaraswamy, argued that the Indian national movement must fight a guerrilla war against the museum. Quoting a Sinhala journalist, he asked: ‘If God were to return today and ask the western man where the Aztecs and the Incas were, would man take God to the museum?’ The museum, Coomaraswamy claimed, smelt of death and formaldehyde; of the dyingness of culture.

Social movements today have discerned in ideas of ‘progress’ and ‘development’ a genocidal emphasis with respect to indigenous ways of knowing. These concepts emphasise a divide between ‘backward’ and ‘advanced’, allowing ‘advanced’ societies to erase or eliminate indigenous and traditional knowledge in the name of progress. In response, some have argued that the Indian Constitution cannot be embedded in linear concepts of time and development, but must instead be located in multiple time.

But why multiple time? With modern development theory has come the tacit imposition of time as something linear and absolute; a progression of events taking place one after another in a neat chronology of past, present, and future. Within this linear perception of time, that which is tribal or traditional is forced towards obsolescence and erasure as a backward entity. A society located in multiple time, however, makes the tribal a contemporary, rather than an ancestor.

Community in plurality

All this raises the question of why cognitive justice sees itself as an addendum or even a challenge to the ideas of the Enlightenment. The slogans of the Enlightenment are embodied in the tenets of the French Revolution – its dreams of liberty, equality, and fraternity. Modern life, especially in the west, emphasises the first two: liberty has come to evoke individual freedoms and rights. Equality has, in its way, led to standardisation and even uniformity.

Fraternity, as a sense of community in plurality, has been the weakest of terms. Western society has little sense of the dialogue of difference or diversity. Tolerance in a liberal sense is too lazy a theory of difference. Compare it to the South African idea that one must invent a stranger every day to sustain difference. The latter is a reminder that, as Lévi-Strauss argued, the self is incomplete in itself. Difference becomes an aesthetic, ethical, and political tool which allows democracy to guard itself against populism and majoritarianism – two afflictions that Indian democracy has been subject to in recent times.

Democracy needs a more robust theory of difference that acknowledges multiple ways of knowing. All societies, not just the post-industrial, must be recognised as knowledge societies. Difference must be understood as more than merely ethnic or ecological: a plurality of knowledge systems is necessary for any democracy based on difference.

The weavers and the scholars

This debate came vividly to life at a meeting a year ago in a little town called Chirala, a short distance from the city of Hyderabad in India. Chirala was to be the scene of a meeting – a seminar between 400 weavers and academics, the latter being scholars of science, technology and history from Europe.

The first few days passed without any surprises. The weavers sat on the floor, the academics on their chairs, and the very body language represented the cognitive distance between the two groups. In a moment of serendipity, one of the Dutch scholars, Weibe Bjiker, suggested that they all sat on the ground. A radical change took place as the two groups started talking. The weavers even brought their looms along, providing a running text to the act of weaving.

From social distance, the seminar moved to a sense of candour between professional and technical equals. As the seminar evolved in this new frame, one of the weavers turned to a historian and said: ‘You have not only destroyed our livelihood, you have taken our theory away from us. You have theorised us out of existence. We need to claim our theory back, to recover our livelihood.’

In this room, a dialogue of difference became the basis of recovery. The documents from Chirala show that the recovery of weaving and the reinvention of colour will be done on the basis of indigenous chemistry, as natural and synthetic dyes dialogue it out. Indigenous knowledge and theory were recognised as a lifegiving part of livelihood and democracy.

Domesticating the alien

Most theories of colonialism fall within the centre-periphery axis: the centre is the source of power for dominant ideas. In a centre/periphery model, one can subvert a dominant idea at best. A contrary theory evolved around the ideas of poet AK Ramanujam and writer UR Anandmurthi. They argued that Indians, in fact south Asian intellectuals, domesticated alien ideas in a playful way.

For Ramanujam, the architecture of the house became a metaphor for this. His father, he said, met colonial and revenue officials in the frontyard of the house. The backyard, on the other hand, which included the kitchen, was the domain of women, cooking, and storytelling. The backyard had a different, more inventive way of domesticating and translating an alien idea. For Ramanujam, Nehru and Jinnah were frontyard intellectuals, whereas Kabir, Nanak, Tagore, and Gandhi embodied backyard styles. In other words, they could ‘domesticate’ western dominance in playful ways.

The forest of knowledges

As a project and thought experiment, cognitive justice realises that democracy needs a wider repertoire of ideas beyond pluralism and multiple time. The first of these is a concept of nature that moves beyond the idea of it as a commodity to become instead an act of trusteeship.

Second, the formal framework of a constitution must coexist with that of a tacit constitution. While a formal constitution is a legal enactment on the role and rules of the state, it leaves behind a world that is recognised but unsaid; the unwritten worldviews which determine its dynamics. A tacit constitution acknowledges the unconscious and unspoken ideas about ecology, technology, and time that underlie a formal framework.

Third, the right to information, while precious, is not enough. Information alone is raw and incomplete. One needs a right to knowledge, to different and diverse ways of knowing. Fourth, we must revive the idea of the ‘knowledge commons’ to challenge the aridity of the information chain. The profit-hungry entrepreneur who discards all that is known in pursuit of incessant innovation is an idiot in the forest of knowledges.

The commons was once a place where villagers shared access to grazing land, timber for building and firewood, and herbs for medicine. More than a collective space for resources, it was a site which sustained skills, competence, and improvisation. It went beyond the idea of individual rights and private property to an idea of collective access; and, while a commons sustained life, it was not an annexe to affluence. This old idea of the commons as a space and metaphor is now being revived online and beyond. Some working in this field have suggested the idea of a knowledge panchayat: a knowledge village, where all citizens meet to debate the future of ideas. Here, the equal exchange of knowledge and ideas becomes fundamental to decision-making.

Present in all this is a sense that democracy needs to be reinvented pluralistically, intellectually, and playfully. The idea of cognitive justice is an invitation to that thought experiment.

Professor (Dr) Shiv Visvanathan is a Professor at Jindal Global Law School and Director of the Centre for the Study of Knowledge Systems at OP Jindal Global University, India.

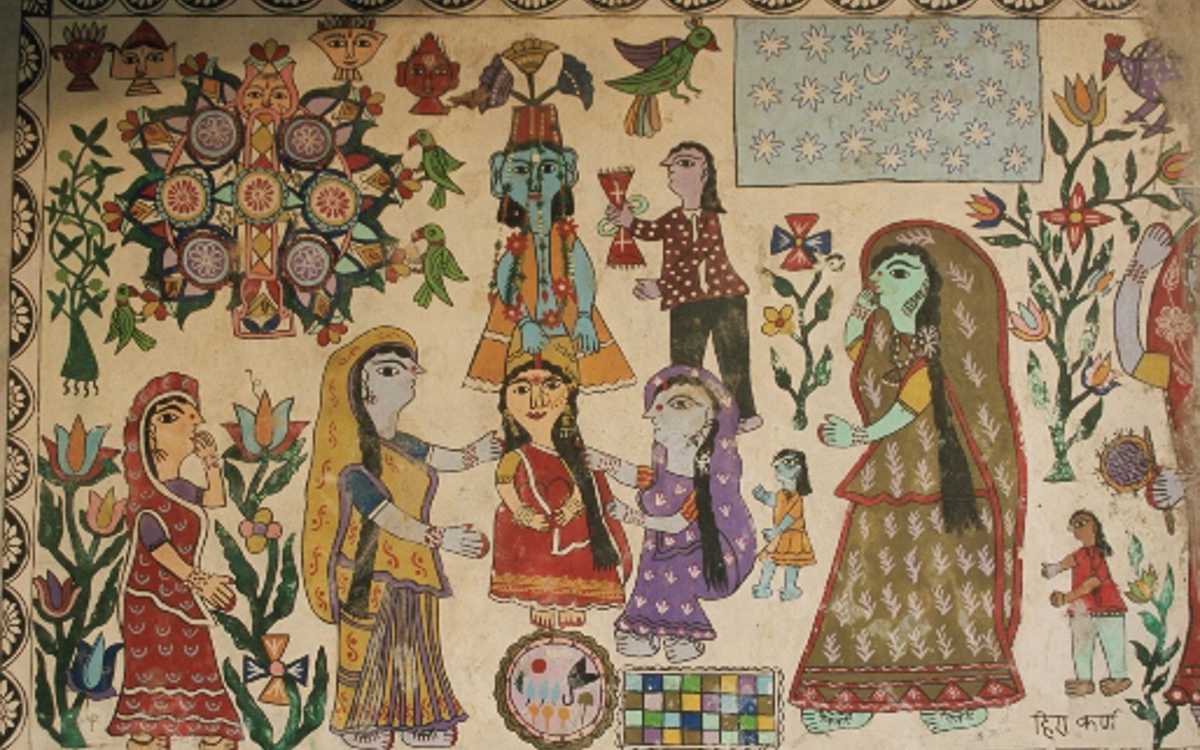

Images (from top): The living tradition of Madhubani painting from the Mithila region of Bihar, photographed by Franck Metois at Alamy. Artist Bharti Dayal describes Madhubani's philosophy as being based on the principle of dualism: ‘Opposites run parallel to each other: life and death, day and night, joy and sorrow, body and soul etc. They are featured in the imagery to represent a holistic universe.’ Handloom by Sk Hasan Ali at Shutterstock